Faculty Senate President Dorothea Herreiner talks to Kirstin Noreen, professor of art history, about the transition to teaching in an online environment. Professor Noreen has taught at LMU since 2006. She typically teaches introductory art history classes and upper-division courses on “Medieval Art,” “Italian Renaissance Art” and “Northern Renaissance Art,” as well as classes through Study Abroad.

Dorothea Herreiner: What is the “Medieval Art” course about and what are your goals when teaching the course?

Kirstin Noreen: This course surveys the major developments in the arts from the rise of Christianity in the Roman Empire in the second and third centuries until the end of the Gothic period in the 14th century. The goal of the class is to examine how social, religious, political, and historical influences affected the development of art and architecture. As a course that fulfills the faith and reason core area, the class is particularly concerned about the interrelationship of religion and visual culture; flagged for information literacy, the class dedicates a substantial amount of time to critical examination of the source material.

DH: What are important disciplinary-specific aspects of this course?

KN: In this course, students explore different methodological approaches to interpreting the visual culture associated with the medieval period. A critical perspective on the art and architecture of the Middle Ages, based on an understanding of the historiography of medieval art history as well as the changing functions and afterlives of monuments, extend the significance of the period beyond the time of an object’s or building’s initial creation.

DH: What are some main lessons you learned this spring, summer, or before about teaching online?

KN: Through online teaching, I have learned the importance of connecting with the students and remaining flexible in my approach. Students were surveyed three times during the summer session to understand their potentially changing technological and learning situations as well as to gauge the workload and effectiveness of instruction. While taught with a synchronous component, the course was also designed with alternative assignments and class recordings in case students were unable to attend the live session due to illness, technological difficulties or other issues. Building in flexibility allowed me to pivot quickly as new situations arose.

DH: What are some main differences between teaching this course in person and teaching it online/remotely?

KN: There are numerous differences with online teaching: the enhanced importance of materials that are clearly organized and easily accessible online; the value of a well-thought out pacing guide; the need for diverse modes of communication with students; and the importance of breaking synchronous sessions into discrete units/activities in order to maintain interest and engagement. Having two monitors allowed me to clearly see my twenty-eight students while also negotiating power point, notes, and multimedia documents.

According to an exit survey for my summer course, students noted the following benefits of the online course: flexibility, the opportunity to take a course from any geographic location, and the ability to replay class sessions. Students stated, however, that they missed interacting directly with other students, they felt that Zoom breakout groups were not as effective as in-person group work, and they missed the opportunity to visit sites such as the Getty Center.

DH: What are some new elements that you introduced into the course in the online environment?

KN: Although already implemented by many professors, I used VoiceThread, the Brightspace discussion boards, Box Notes, and break-out rooms in Zoom for the first time when teaching online. My course, along with several other classes in art history, was also the focus of an LMU Open/Alternative Textbook Initiative Grant. This grant was particularly well-timed, since it pushed me to explore new, low/no cost learning materials. While I already have used 360-degree videos, virtual recreations of monuments, and interactive architectural plans in previous versions of this class, it was imperative to integrate additional, engaging texts and materials for the online course environment. Fortunately, there are many ways to explore medieval art online, allowing students to delve deeper into the role of light and sound in Hagia Sophia, Viking tombs, pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela, or the architectural innovation of a Gothic church.

Blog posts and articles focusing on gender, race, and religious diversity helped to expand our understanding the medieval period and promote discussion during class sessions, as in an analysis of manuscripts by curators at the Getty Center, a discussion of the far right’s use of medieval art, or an examination of the restoration and contemporary function of buildings like the Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba. Class discussions, related to virtual pilgrimage or monastic scriptoria, took on new meaning during the online course when students were practicing social distancing.

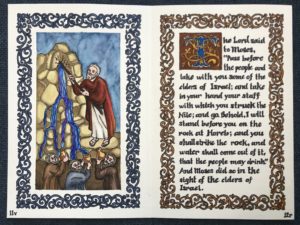

An assignment focusing on medieval manuscript production was particularly effective this summer. Students learned about illuminated manuscripts by creating their own bifolium, two facing pages reproducing a biblical passage. In addition to learning about how to lay out text and images, many students made their own pigments using materials available at home, like plants, natural materials, or spices. One student’s work, by Lucille Njoo, was particularly effective. Rather than the typical use of tempera paint for medieval manuscript production, Lucille experimented with aloe and starch as binding agents for the crushed pigments that made up the paints used to illustrate a passage from Exodus (17:5-6).

DH: What are you most excited about in this course this semester?

KN: Although not tied directly to the online environment, I was most excited about changes made to my class readings to present a more comprehensive, global, and diverse approach to the visual culture of the Middle Ages and to explore connections between the medieval period and our contemporary society. Students examined the adoption of Celtic imagery and Viking culture by white supremacists; questioned the contemporary function of buildings, like Hagia Sophia in Istanbul or the Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba, that have served diverse religious groups; explored medieval concepts and representations of race; and considered the representation of sexuality and gender in medieval manuscripts. Students additionally examined the historical accuracy of the depiction of the Middle Ages in popular culture – like movies and video games – to explore broader issues of race, exclusion, and religious diversity.

DH: What innovative opportunities does this new teaching environment provide?

KN: The online environment has pushed me and other professors in art history to rethink our assignments, presentation of course content, and teaching materials. Pedagogical discussions during the LMU eTraining course, art history-specific webinars dealing with online teaching, and my new understanding of online platforms will certainly have an impact not only on my teaching in the fall, but also when I return to my classroom at LMU.

Although disconnected physically, students can provide unique insights for learning based on their particular locations. When discussing medieval pilgrimage, specifically the Hajj to Mecca, I had several students in Saudi Arabia who were able to speak to their families’ own experiences of that annual pilgrimage as well as changes implemented due to COVID-19.

DH: What would you like to suggest to your students for taking courses in the fall?

KN: The increased independence that comes with online classes necessitates a greater commitment to staying on top of deadlines, being in contact with the professor, and asking questions during class, via email or during Zoom office hours. According to one of my summer school students: “Talk to your professor early on about your circumstances, of your education, so they can try to help you get over any barriers.”

Top image: Noreen’s students examined the restoration and contemporary function of buildings like the Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba in her Medieval Art course.