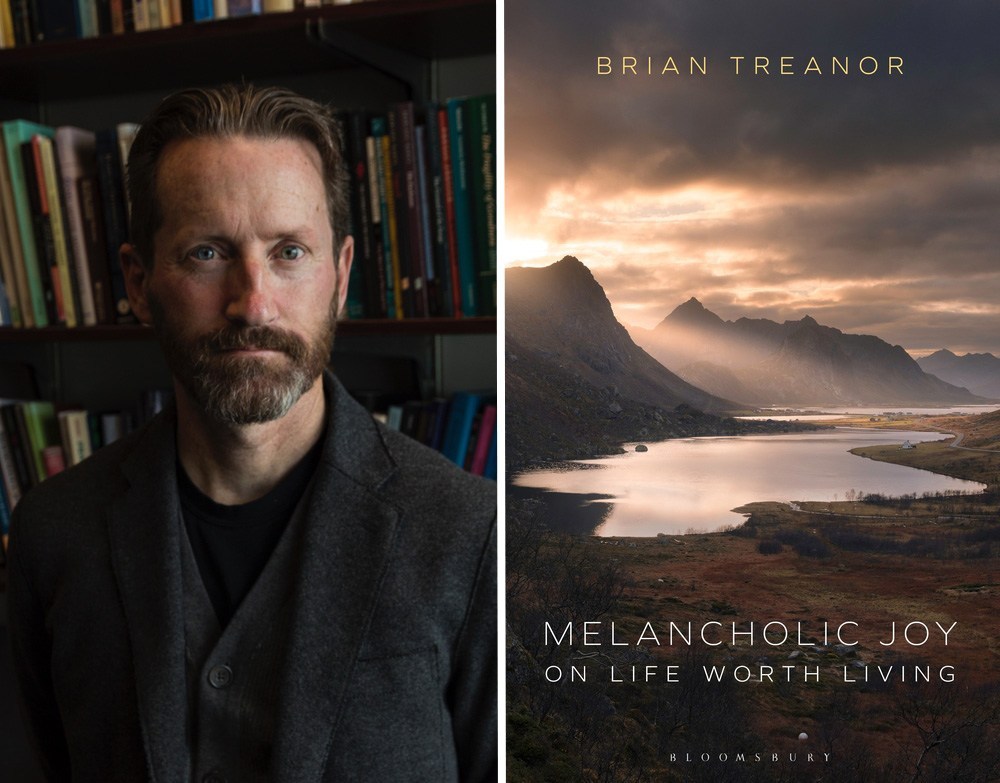

Professor Brian Treanor, a member of the philosophy faculty at Loyola Marymount University for 18 years, has a broad range of teaching and research interests including identity, otherness, nature, wilderness, toleration, forgiveness, hope, virtue, flourishing, God, prayer, place, narrative, embodiment, politics, hospitality, faith, love, and simplicity. His diverse interests have led to various roles within the Bellarmine College of Liberal Arts and across the university. He currently holds the Charles S. Casassa Chair of Catholic Social Values and is an affiliated faculty member of the Irish Studies and Environmental Studies programs. He was also the founding director of LMU’s Environmental Studies program, as well as the Academy for Catholic Thought and Imagination, an interdisciplinary research institute that seeks to encourage intellectual dialogue at LMU, and to support faculty scholarship on a wide range of topics in the humanities, social sciences, arts, and sciences.

Treanor’s latest book “Melancholic Joy: On Life Worth Living,” draws from poetry, literature, film, and even nature, to provide an honest assessment of the human condition. It unflinchingly acknowledges the everyday frustrations and extraordinary horrors that generate despair and argues that the appropriate response is to take up joy again, not in an attempt to ignore or dismiss evil, but rather as part of a “melancholic joy” that accepts the mystery of a world both beautiful and brutal. The book is available HERE and the first chapter of the book is available to read for free HERE.

We caught up with Treanor to discuss the book and its arrival, which couldn’t feel more timely after several months of fraught daily living.

What made you want to write “Melancholic Joy”? I know you have taught at LMU for 18 years, did the idea for the book grow out of any particular lectures you have given, or courses you have taught?

I’m not sure if there was any one particular thing that made me “want to write” Melancholic Joy. Writing, for me, is part of thinking; it’s part of the process of coming to sort out just what I think about things. In this instance, I guess I was trying to come to terms with whether, fundamentally, reality counsels despair or joy. So, I suspect part of why I wrote the book was to sort out just how we should respond to a world in which loss, suffering, and evil seem to be omnipresent and, indeed, seem to have the last word, but also a world in which goodness and beauty seem to be ineradicable. I think that most people lean toward either pessimism or optimism far, far too easily and unreflectively. Either they explain away the evil so as to be comforted by the good, or they miss the goodness and wonder from obsessing over the evil. But both pessimism and optimism are distortions of reality. Toward the end of Melancholic Joy, I write: “Something is wrong with either your eyes or your heart if you do not experience, profoundly, both the joy and the sorrow of this world. On the one hand, it would take monstrous egotism, cold indifference, or willful and cowardly ignorance not to have your heart broken and your soul wrung by the obscene suffering woven into the fabric of being, and magnified by human vice; and, on the other hand, it would take appalling insensitivity or cultivated shallowness not to be moved to tears by the overflowing, gratuitous, miraculous beauty of it all.”

What did the writing process look like? How did other areas of your life, or interests, contribute to the writing process, or ideas in this book?

It took me perhaps three to four times longer to write this book than any of my others. It deals with very personal, very human, issues. I wanted to write the book in a way that would be serious, but which would also be accessible to non-specialist readers. That’s one of the reasons I went with Bloomsbury as a publisher. Likewise, I was at pains to make the project palatable to a wide range of people. So, for example, I don’t deploy any traditional faith-based tools for dealing with evil. In fact, I explicitly reject simple forms of theodicy, perhaps the most well-established philosophical response to evil. I wanted the vision of the book to appeal to people whether they are atheist, agnostic, or theist. I think it was also a long process because, once you start thinking about the evil in the world—really thinking about it, not just denouncing it or railing against it—things get dark pretty quickly. That’s one reason I think most people don’t really dwell on it. They take comfort far too easily in the mechanical belief that the arc of the universe bends toward justice or salvation. Well, perhaps. But there are also reasons to suspect or worry that it does not. Moreover, the mechanical nature of their hope or faith also means that they miss really seeing, experiencing, or appreciating the wonder of things. It’s probably not the best selling point for a book, but I generally think that people should feel both joy and desolation more keenly, and with a bit more appreciation for the reasons to feel each. Hence the title of the book. I think when we look at the full scope of reality—both the beauty and the brutality—the mature, honest response is one of “melancholic joy.”

What are some concrete ways we can find joy in the ordinary, in our suffering, and no matter what the circumstances may be?

That’s a good question. What we need to do is cultivate “new eyes,” new sensitivity and receptivity to the miracle that things are rather than are-not, and to their ephemeral nature, that fact that at some point they will-not-be. Plenty of other people have made similar observations: Annie Dillard, Nikos Kazantzakis, Erazim Kohák, et al. Philosopher Pierre Hadot says it is a matter of developing the ability to see the world, simultaneously, “as if for the first time” and “as if for the last time.” One perspective allows us see the world with wonder. When we can do this, the world becomes new again, a world, as Wallace Stegner writes of Norman Maclean’s childhood in the American West, “with dew still on it… younger, fresher, and more touched with wonder and possibility.” The other perspective reminds us that, ultimately, all of this comes to an end. There is, of course, a sadness that comes with that realization; but we can look at the ephemerality of beauty with gratitude as well. It’s the vision of a person who has been given one last, unexpected day with a lover before shipping off to war, of someone with a terminal disease given six months of remission by an experimental treatment. For such people, attention to every detail of the world is enhanced. In the book I’ve got a lot more to say about how to cultivate these “new eyes,” but that’s the gist of it.

How have the arts, particularly the writing of Virginia Woolf, the poetry of Jack Gilbert, and the films of Terrence Malick, contributed to your understanding of the human condition?

I’m happy to be a philosopher, but I am an interdisciplinary thinker by nature. And, frankly, I think that the issues I take up in this book are dealt with much better in literature and poetry than they are in philosophy. Engaging literature and poetry philosophically can bring a different kind of rigor to the issues; but, for questions about the lived and felt meaningfulness or meaninglessness of life, you’ve got to go to the poets. As French philosopher Michel Serres observes: only philosophy goes deep enough to demonstrate that literature goes still deeper than philosophy. Another reason I wanted to draw deeply from literature and poetry, as well as film and personal experience, is to give as many different people as possible a way “into” the issue. For example, one chapter develops a phenomenological and philosophical account of the joy of the active body in the material world, which any physically active person should be able to relate to. Another chapter draws on films, stories, and poems to explore joy and despair in small, everyday moments. Another chapter explores the experience of love, and extends traditional accounts to think about love of nature.

I know the book was written before COVID-19, but its messages and themes couldn’t be more apropos! What do you hope people reading “Melancholic Joy” takeaway and apply to their lives, especially during this time of pandemic and economic/social/political unrest?

I I do think that the past year has made the book more, not less, relevant. I actually wrote a Preface about this, but Bloomsbury did not want to “date” the book and we decided to remove it. On the one hand, a year like 2020 is bound to make us all more appreciative of the precariousness of things. We’ve been reminded that whatever kind of privilege we have—and we all enjoy the privilege of life, of being rather than not-being—that privilege is fragile, uncertain, and temporary. There’s just one end to our story. If people are reflective, they are probably a bit more aware of the fact that any given day could be the day the “big one” destroys Los Angeles, or the doctor tells me “I’m sorry, it’s malignant,” or I lose a family member. And, more, the fact that one day each of those things will happen. And it’s only a short step from there to wondering if any of it matters at all. But that’s nothing new. The temptation to despair has always been with us and will always be with us. Those who claim that the evil represented by COVID-19 is “unprecedented” are suffering from a bout of historical myopia. The “Spanish” Flu of 1918—recent enough that a few survivors are still with us during the current pandemic—likely killed over 50 million people. The successive waves of plague that swept Europe in the 14th century may have killed as much as sixty percent of the population. Some estimates suggest that the introduction of smallpox, typhus, measles, flu, and other diseases to the Americas killed upwards of ninety percent of the First Nations in the worst-affected areas, wiping out entire civilizations in the process and changing ecosystems so profoundly that it may have temporarily affected the very climate of the earth. However, even in the midst of the pandemic, people are experiencing and sharing moments of hope and love. Despite fear and uncertainty, people are risking themselves or aiding others in ways both large and small: frontline medical workers returning each day to the ICUs; young people who deliver staples to the elderly and vulnerable; neighbors sharing resources; an ad-hoc family string quartet playing for their apartment block from the balcony; myriad forms of virtual art and culture distributed freely; and more. Despite the challenges of isolation—the monotony of routine, the depressing weight of confinement—people find themselves reconnecting with the small miracles of the everyday. As the pandemic raged in hotspots around the world, causing suffering and anxiety that we cannot ignore or forget, people were also able to slow down, reconnect with family and friends, and take pleasure simple routines. Artists collaborated and created. Lovers courted and consummated. Babies were born and children were nurtured. The seasons turned, showers fell, flowers bloomed. Bioluminescent surf lit up the darkness in southern California. The skies over Delhi and other major cities became clearer than they had been in generations, the canals of Venice and other waterways flowed limpid and tranquil, and animals flourished with newfound abandon in a world in which, for the moment, human pressure was felt more lightly. This is no sentimental bromide. It’s real. T.S. Eliot wrote that humans “cannot bear very much reality”; but sometimes what drives us to despair is precisely not enough reality, in the sense that we often allow one aspect of reality (i.e., that which we experience as a burden, threat, or loss) to occlude another (i.e., that which we experience as a gift or a grace).