Bryant Keith Alexander, dean of Loyola Marymount University’s College of Communication and Fine Arts and professor of communication, performance and cultural studies, is an active scholar with a distinguished record of teaching, service, professional activity, and a regular performer and keynote speaker at universities and conferences around the country. His nearly 200 scholarly publications appear in leading journals, edited volumes, and major handbooks that evidence the broad interdisciplinary and intellectual curiosity of his engagement. This interview was conducted on the occasion of Alexander’s most recent publication, “Intergenerational Dialogues of a Black Quartet: Qualitative Inquiries on Race, Gender, Sexualities, and Culture” (Routledge, 2022), which he co-authored with Mary E. Weems, Dominique C. Hill, and Durrell M. Callier.

Question: This is such a ground-breaking collection. How was the project first conceived? How did the four voices come together to collaborate and converse in this distinct way?

Bryant Keith Alexander: The project came together in a very organic way, linked with a deep and abiding love and respect between the four scholar-artists. Mary E. Weems and I had completed two lauded, co-edited, special journal issues; one on the current crisis at the intersection of COVID-19, presidential leadership, and Black Lives Matter.[1] The preceding was on terrorism and hate after the Orlando massacre. We then completed two co-authored books, Still Hanging: Using Performance Texts to Deconstruct Racism” (Brill | Sense Publishing, 2021) and Collaborative Spirit-Writing Performance in Everyday Black Lives (New York: Routledge, 2021).[2] In the process we confirmed a rhythm of engagement in writing and in our shared commitment to cultural celebration and social critique. At the same time Dominque Hill and Durell Callier, the younger of the quartet, had been in a long-time collaborative partnership in writing, performance, and cultural activism producing a book, Who Look Like Me?! Shifting the Gaze of Education through Blackness Queerness and the Body (Brill | Sense, 2019).

Our decision to collaborate on the book project was an extension of our deep respect for each other as teacher-artist-writer-scholars, and a recognition of the intergenerational dialogues that was already present in our scholarship, both individually and in relation to those established dyads of engagement. I initially pulled the group together to further the dynamism of that kinetic creativity in a performance panel titled, “A Black Quartet: Performing Collaborative Liberation” at the 2020 International Congress of Qualitative Inquiry (ICQI). The collaboration was so synergistic and rewarding that I immediately announced at the end of the performance, much to their chagrin, that we were moving the collaboration to a book length project. And the work immediately began, using our script from the performance as the cornerstone for the proposal to Routledge. As the book was in press, we returned to the ICQI conference with a panel titled “A Black Quartet II: Collaboratively Performing Transformative Visions,” where we presented more work and announced the publication of the book — which unfolded quickly like any rich and deeply invested dialogue between friends and colleagues across age, time, and distance.

Q: How do you see this project and your contribution paying homage to the Black scholars who came before you, and those who are seeking to follow in your footsteps?

Alexander: The project is an homage to four particular Black playwrights and the Black cultural communities of our rearing and raising. First, the 1970 book A Black Quartet is a collection of four emerging Black playwrights: Ben Caldwell, Ronald Milner, Ed Bullins, and LeRoi Jones. The subtitle of the book states: “A revolution is now taking place on stage.” The book presented four new Black plays from the Black playwrights including “Prayer Meeting or, The First Militant Minister” – a one-act play by Ben Caldwell, “The Warning – A Theme for Linda” – a one-act play in four scenes by Ronald Milner, “The Gentleman Caller” – a parable in one act by Ed Bullins, and “Great Goodness of Life” – A Coon Show, by LeRoi Jones.” The back cover of the book reads in part, “For the first time American black playwrights have found their own true voice—and are using it. With pride. With confidence. With defiance. With awesome power.”

Our book signifies the importance of the originating “Black Quartet” book, a collection of plays, as a hallmark of Black theatre excellence — to extend the dialogue through the prisms and potentialities of four Black teacher-artist-scholars operating within the constructs of higher education and as public intellectuals. Second, the varying pieces of the project is an invocation of lessons learned from the biological family and our learning in the cultural caldrons of the differing Black communities of our growing and knowing. We give celebration to parents and grandparents, sistas and brothas; to those who mattered; to monuments, memory, and remorse in our cultural and personal lives, as we extend a cultural critique of social politics through a Black perspective.

The very premise of the book is grounded in an intergenerational dialogue between two broadly constructed generational divides of the authors; but as we speak to each other we are also speaking back to the Black ancestors, to our present Black contemporaries in the current cultural zeitgeist, and to a Black futurity that speaks to the next generation.

This project is an homage to four particular Black playwrights and the Black cultural communities of our rearing and rising.

Q: How do you see yourself as a Black scholar-artist placed between the living and the dead? What do you think is the role of recognizing the complexities of our histories? What do you think is the responsibility of the Black scholar-artist in this regard?

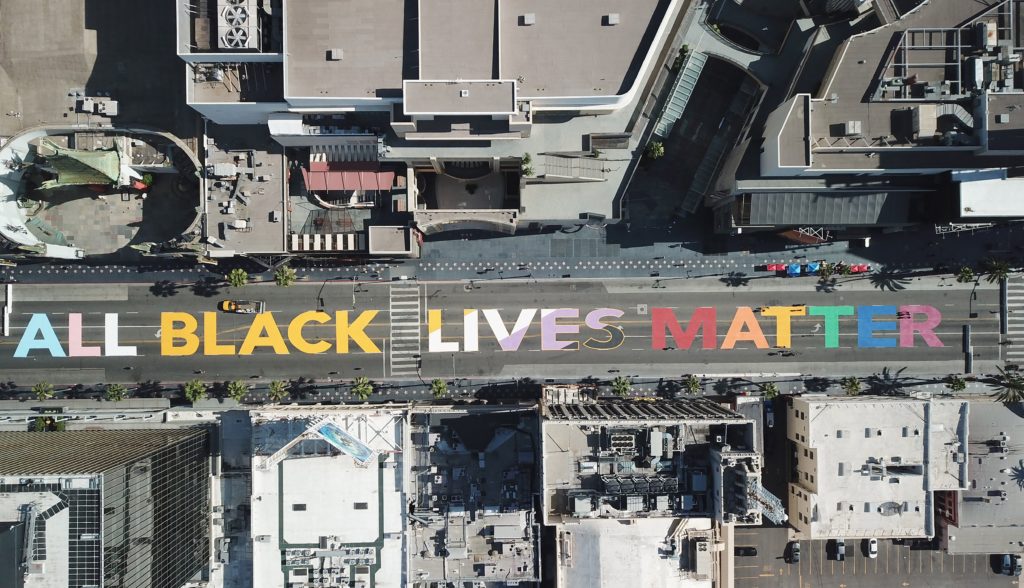

Alexander: We exist because they persisted, and those who follow us will exist because we stood in the gap, bridging our past to their future. The complexity of our Black history is written in the sinews of our bodies, marked on the materiality of our skin, and regulated in the rhythms of our breathing; even as some of our brothers and sisters gasp for breath in the continued attacks on Black bodies in this country. The role of recognizing the complexities of our histories is recognizing that because of slavery, we are an anomaly of presence in this country to which we are consistently trying to recover in our shouts that ‘Black Lives Matter.’ We come from a rich history of people who were free to live, thrive and breath; and at the conjunction of the middle passage (our past, through slavery, and the present) we are commanded by the ancestors to fulfill our destiny of greatness, to speak, to write, to act upon, and fulfill our potentialities as Black humans reshaping the world for good. In that process,the responsibility of the Black Scholar-Artist in this regard is to narrate our past and shine a critical light on our current realities with honesty– in a voice that is both sophisticated and clearly accessible to our diverse brethren so that they can see, read, and engage our collective story—then contribute to it through diverse modalities of Black cultural expressivity. For a new Black futurity.

Q: Can you speak about this intentionality of representing intersectionality in the work? How did you and the other contributors manage to do this, in a way that strives to represent the diverse array of Black voices, and beyond?

Alexander: For a moment I want to shift from the concept of “intersectionality” to the notion of “dense particularity.” I believe that it is Satya Mohanty who uses this concept and sometimes I like it better than intersectionality in this current cultural and political climate. I like dense particularity because the language references the politics of locationality, not just a meeting place of oppressions but as a palimpsest of histories and characteristics of the self, born through history but maybe also the volition of claiming and renaming ourselves. For me, the term addresses how we define our particularity of self through strife and self-crafting, and through the sedimented aspects that inform our being.

So, if I am to respond to your question: Each of the contributors bring their dense particularity to bear upon and influence this project; the evidence exists in the dialogue, in the differing perspectives, modalities and narrations of our Black experience. Blackness, not as a monolith but informed by differing cultural practices made manifest in place and space, in voice and volition; and in the informing aspects of being and becoming Black. Then, the address and redress of how one re/presents that journey to/in the world in ways that are same-and-not the same; but speaks to the dynamism and difference in Black culture. So, within this project, you see and hear a “call and response” between the authors that is undergirded by cultural familiarity and recognition, without a recognition in/of the diverse expressions of Black performativities. As such, we remind and respect each other, while signaling the intersectionalities of blackness without relegating ourselves to just the oppressions of those historical truisms; but the richness of being Black, and then turning our faces towards futurity with an invitation to the reader to contemplate potentiality.

Q: In your essay “Standing at the Intersection of 38th Street E and Chicago Avenue S,” you reckon with being a Black man at the location where George Floyd was murdered. What does it mean to find yourself in such a location? What is its implication, and what do you think is the significance it carries for others who carry this trauma in different ways?

Alexander: In some ways, the location of George Floyd’s murder is synecdoche in the lives of Black people in America. Its location stands as a figural representation; a part that represents the diverse locations of Black trauma in our history in this country. Standing in that location is a painful recognition of walking/driving while Black in anywhere USA. The recognition of tragedy in that location is a remembrance of Black trauma and loss in No Name City, USA, or wherever you live, and where I roam. It is a memorial site where we remember ourselves in relation to the departed; where we say prayers and make promises about the future; where we mourn and gain strength in survival and the activist affect that we embody that will continue to push for change. His traumatic end is the reminder of the trauma that all Black people live with, live through, and struggle against, daily — it is a reminder and a place of reckoning as we recover and seek reparations.

Q: In your essay “Feeling Real,” you talk about what you call Monuments of Remorse. Can you talk more about this, and what it means to you to be a representative for others, what it means for you to be an agent of change for others?

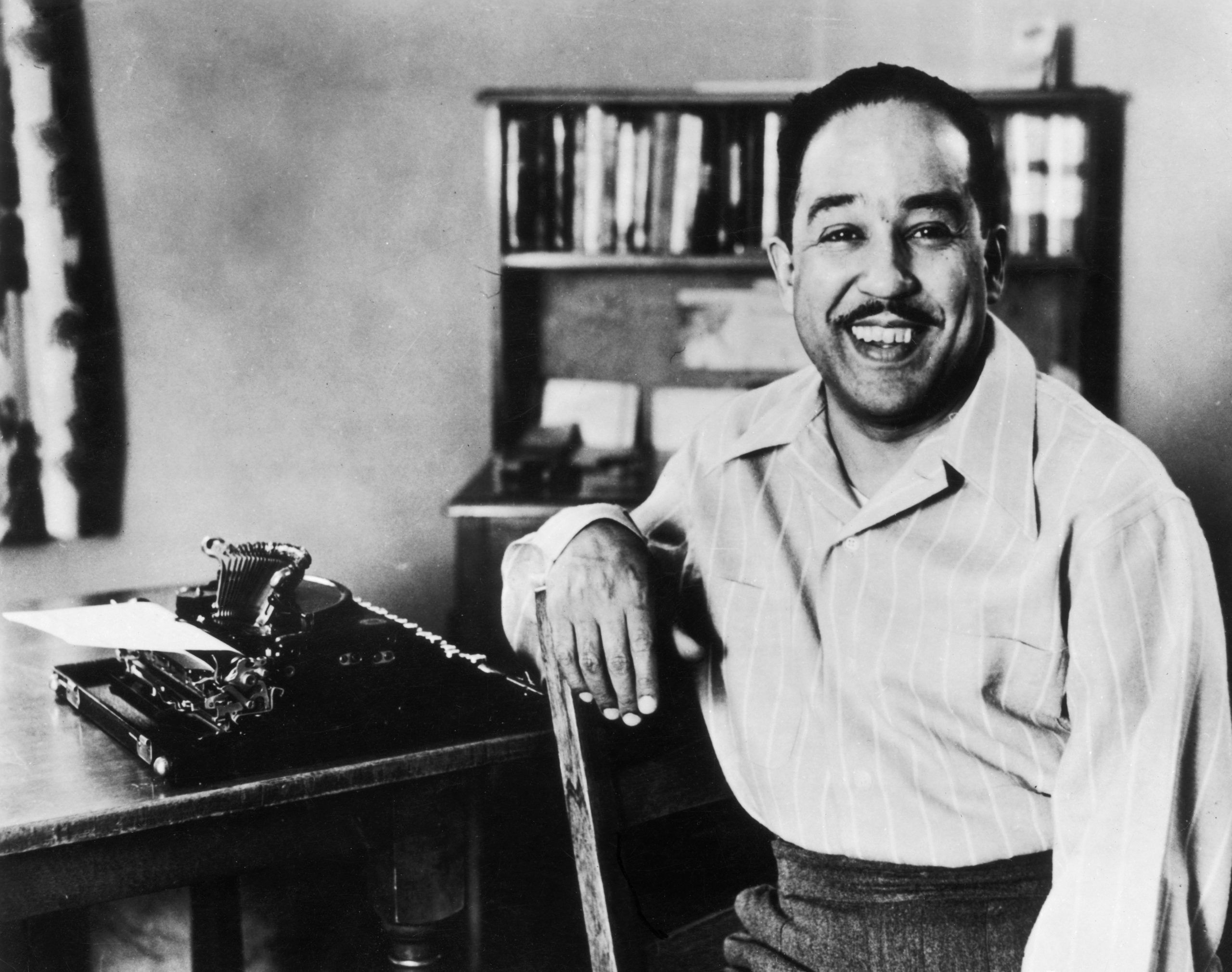

Alexander: The short essay that you reference is a response to a preceding entry of my young Black brother and co-author Durrell Callier. In the performance script embedded in the introduction of the book, in a section titled “Feelin’ Real/Unbroken)”[3] he states: “Nobody ever told me Langston Hughes was queer.” He then follows with a commentary on intergenerational Black gay/queer men (teachers, artists, poets, scholars). And for me, he triggers the query of what we know and don’t know of their lives, what we learn and don’t learn about ourselves in relation to what we know and don’t know about them; and what we share and don’t share in public spaces about our lives that could inform our younger Black queer/gay siblings. My entry in many ways is an apology to him and other young Black gay brothers/sisters and those who live in between and in transition to their own becoming. An apology of not telling them that Langston was gay, and more pronouncedly, that I am gay. While I was never closeted, the apology is really about the representational politics of giving voice to truth for self and other as an activism. I would like to think that I have always been a role model for some through a PRIDE-filled carriage of myself. But my apology to him, and other cloistered queer readers, was also prompted as a moment of critical remembrance of my own upbringing — and the knowing and not knowing.

When I first heard the phrase “Nobody ever told me Langston Hughes was queer” — coming from his mouth in performance — I teared up. I began to cry from a deeply felt remembrance of the things that I did not know growing up as a young Black gay boy in the South. I took his articulation as a charge for the power and importance of representation. Representation as a volitional act that evidences the self for others; representation as a signal of possibility to others; representation as a potential projection of the possible and the potential for those who are searching for role models who look like them in every facet of living; representation as a volitional act of putting oneself OUT there to be seen and known as a template of sociality. Not to be mimicked and copied, but to show diverse realities of being that can inform choice and possibility, that encourages self-love—in ways that are productive to toward a pride-f way of living; and being fully alive. And in the case of the Black gay/queer to know that you are made in God’s image, which is both particular and plural to all his children.

Q: How do you hope students will engage with this important work? What are some ways that students can continue to engage in such qualitative inquiry?

Alexander: In many ways this project is written through an autoethnographic methodological approach. Autoethnography is a culture-centered qualitative methodology that foregrounds individual voice to make articulations about cultural experience as a curative for what ails us. I believe that autoethnography innately engages in resistance. To critically articulate and examine lived experience, not as the oft critique of naval gazing, but as the illumination of experience in cultural systems often of trauma or oppression, as a politic of evidence using the body and lived experience as evidence. Providing both autoethnographers and audiences a pragmatic, accessible way of representing research, a way that devotes itself within grounded, everyday life. This process of engaging autoethnography in any given situation is a close analysis of lived experience through the thrice engaged processes of reflectivity, reflexivity, and refractivity; the turning of a critical eye to past experiences relocating the self momentarily in the past in an act of critical remembrance with an intention of gaining insight for the refractive possibilities of bending time/light/energy for future change and transformation of self, culture, and society.

This form of writing through and theorizing lived experience is both important as a cathartic reexamination of the self, as well as a powerful articulation of lived experience that can offer others a perspective and a politic of culture that is not otherwise accessible to them. It can also serve as a mirror for others that offsets the often-felt sense of isolation that we all feel at times through trauma, believing that we are alone. It can also be used as a tool for advocacy and activism, when we engage in the processes of information, formation and transformation of self and society that undergird both the education of the whole person, and the recognition of the unique experiences that shape all our dense particularity. And for members of a Jesuit academic community — this should sound very familiar. I want students who engage this work to use as a tool or invitation to generate their own stories; and to begin to explicate their own truths.

In some ways, the location of George Floyd’s murder is a synecdoche in the lives of Black people in America. Its location stands as a figural representation; a part that represents the diverse locations of Black trauma in our history in this country.

Q: What other projects are you currently working on that you’d like to share?

Alexander: I am currently working on two essays that are informing a larger book project. One essay is currently titled, “Onboarding, Orientation, and Mentoring as Culture-Crafting Processes: A Rac(e)y Autoethnography of Resistance in Higher Education Administration.” The other project is playfully, but critically titled “Fat Asses, Weight Gain, and the White Feminine Commodification (Contortion) of Black Female Bounty.” You can tell from the titles that the focus of my interests is always linked to representational issues of race in shifting cultural contexts from issues of diversity, equity, inclusion, and anti-racism in higher education to the historical mischaracterization of the Black female body as social foil. Each piece continues to use autoethnography as a framework of articulating experience and the relationality of racial bias as it manifests on differing bodies through a critical lens of experience and observation. These essays, which are promised to be published in separate places within the year, are working in conjunction with a recently published essay, “A Warning/A Call: The Spectacle of (In)Visibility in the Vernacular Response to DEI-A Work,” to inform the yet to be named next book project.

Q: How you do you think the LMU community at large can continue to engage in such inquiries, and continue to foster an environment where such rich and necessary conversations can take place?

Alexander: There are a lot of important programs and resources that have been developed and provided to the LMU campus community through Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. The resource page is very impressive. And there are open invitations for people to get involved through conversation groups, work teams, the transformation and decolonizing of curriculum, college/school-based DEI committees and officers; along with the revisioning of evaluative standards that govern every aspect of university and academic operations. The key for me is for people to share authentic stories of lived experience as to make palpable the impacts of their encounters with racism and other forms of bias, in which we may all be implicated in one way or another. This leads to open spaces of healing, and, where possible, encourages reconciliation, because the effects of all forms of bias impacts all aspects of our personal and professional lives — along with our sense of community and belonging, which must be continually cultivated and assessed. Community is more relational and less locational. How do we further dynamize the service of faith and the promotion of justice through critically recognizing our unique stories? Stories that inform our dense particularity (same and not the same) in the plurality of a faith-based academic environment.

[1] Alexander, B. K., and Weems, M. E., (2022), Editor, Special Issue, “Critical and Performative Reflections on Current Crises,” Cultural Studies; Critical Methodologies, with Mary E. Weems (12 entries). Volume 22, Issue 4, Alexander, B. K. and Weems, M. E. (2017). Editor, Special Issue, Terrorism and Hate in Orlando, America (Poetic and Performative Responses), Qualitative Inquiry, 23.7: 483-571.

[2] Alexander, B. K. and M. E. Weems (2021). Collaborative Spirit-Writing Performance in Everyday Black Lives, New York: Routledge. In the Qualitative Inquiry and Social Justice Series Books, edited by Norman K. Denzin and Yvonne Lincoln; Alexander, B. K. and M. E. Weems (2021). Still Hanging: Using Performance Texts to Deconstruct Racism, Brill | Sense Publishing. In the Personal/Public Scholarship series edited by Patricia Leavy.

[3] Durell Callier’s contribution to “A Black Quartet” is drawn from his essay: Callier D.M., (2020). “Feelin’ Real/Unbroken: Imagining Blackqueer Education Through Autopoetic Inquiry.” International Review of Qualitative Research. November 2020.