An extra-constitutional change has occurred in the past 30 years that, while hardly noticed, has dramatically changed the way we are governed.

The United States holds national elections every two years. All members of the House of Representatives run in each of those elections as they hold office for a two-year term. Senators are elected to six-year terms, and one third of the Senate is up for election every two years. Presidential elections occur every four years. This staggering of elections was designed by the framers to resist abrupt, sudden changes that might reflect the passions or whims of the moment. Their goal was not to establish an efficient government but to create one that would slow the course of change, and protect liberty.

This staggering of elections was designed by the framers to resist abrupt, sudden changes that might reflect the passions or whims of the moment.

This means that each time a president is elected, two thirds of the Senate – elected in previous elections – remain in office despite a potentially new president and a new course for the nation for which the public votes. Compounding the dilemma for a new president is the fact that even in mandate elections, remnants of the old order remain entrenched in power. This is further compounded by the fact that in mid-term elections, the president’s party almost always loses a significant number of seats in both the House and Senate. This all-too predictable cycle of victory then (two years later) loss, gives the president a two-year window in which to pass landmark legislation, as after the mid-term losses, presidential power is diminished and legislative prospects limited if not thwarted.

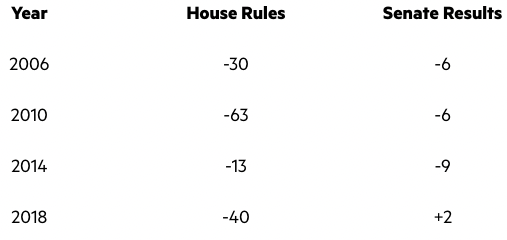

This creates a new phenomenon: the two-year presidency. Presidents have two years to get their legislative programs through a Congress usually, though not always, controlled by their party. After the mid-terms, the president is often hamstrung by one or both Houses in the hands of the political opposition, an opposition usually unwilling to work with the president. Results from the last four mid-term elections bear this out.

Why this mid-term fallout? In the first few years, presidents build up some resentments from the losers in the political process, plus, they begin to own the nation’s problems. Inflation? It belongs to the incumbent president. Climate change? Blame the president. The mid-term is a referendum on the incumbent, and all problems seem to be blamed on the president. Plus, mid-term elections have lower voter turnout than presidential year elections and that means that highly motivated voters turn out at relatively higher numbers. And in our deeply divided and divisive society, the phenomenon of “negative partisanship” (voters voting “against” the people or party they dislike rather than “for” things or people they believe in) has become more common.

If past is prelude, incumbent presidents will lose on average 28 seats in the House, and four Senate seats. And most of the time, one part of the legislative branch majority shifts to the opposition party. If the Democrats face a 2022 mid-term in this range, they will lose control of both the House and Senate, and thereby, President Biden will lose control of the agenda, hemorrhage power in Congress, and be largely unable to get his legislative agenda passed by a Congress controlled by the Republicans. It is a dilemma his predecessors faced as well. How did Biden’s predecessors respond?

The presidencies of George W. Bush, Barack Obama, Donald J. Trump reveal that in their first two years in office, all did reasonably well in getting their key legislative proposals passed into law. But in the last two years of their terms, they got virtually nothing from Congress.

What are the consequences of this two-year presidency? It has meant that presidents must get everything they can from Congress in the first two years, then find an “alternative” method of governing for the last two years of their term. Presidents recognize these very different seasons of power, and shift from a legislative strategy to an administrative strategy. Same president, different presidencies.

What are the consequences of this two-year presidency? It has meant that presidents must get everything they can from Congress in the first two years, then find an “alternative” method of governing for the last two years of their term.

It isn’t supposed to be this way. The constitutional model of political change embedded into our governing documents calls for the development of consensus that leads to bargaining and compromise, and ultimately, legislation. This textbook version of American politics works only in the first two years of a new president’s term, when the president commands partisan majorities in one or both chamber of Congress. And in the last two years, rather than be stymied by the political opposition, presidents develop extra-constitutional methods of governing. This usually means using the managerial or administrative tools of a president’s arsenal. These tools (executive orders, proclamations, signing statements, administrative rulemaking, etc.) mean that the president attempts to exercise unilateral powers bypassing Congress and governing alone. Democrat and Republican presidents do this, and if you are the incumbent, it makes political sense. But it does constitutional violence and undermines democratic norms.

Is there a way out of this dilemma? Does the staggering of elections make sense any longer? And will (can) our dysfunctional hyper-partisanship be reduced? I am old enough to remember when – on occasion – Democrats and Republicans worked together on key legislative matters. But today, even having a friendly chat with a member of the opposition party is seen as a sign of disloyalty. Our political system seems broken because we allow it – even encourage it – to remain broken. If “we” change, our legislators will change. But as long as partisan hatreds animate voters, we will be stuck with the dilemma of the two-year presidency.