My first day at the White House started with 5:30 a.m. coffee — in reach but out of frame, in the hastily tidied, Zoom-friendly corner of a spare bedroom in Los Angeles.

It was April 2021, a few days before COVID-19 vaccines were generally available in California, and three months after the Confederate flag gained an entry to the Capitol it had never managed during the Civil War. I’d been asked to serve as the inaugural White House Senior Policy Advisor for Democracy and Voting Rights. These were unusual times.

This was the second time that LMU Loyola Law School, with its proud tradition of fostering public service, had loaned me to the federal government. A few years earlier, I’d served in the leadership offices of the Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division, supporting career attorneys’ work to enforce statutes protecting voting rights and combating employment discrimination. I reported to an extraordinary woman of color reporting to an extraordinary woman of color. In the White House, with different personnel, I found I had the same happy structure.

The position sat on a policy team devoted to racial justice and equity; emphatically the right place for a position on democracy. This administration recognizes the importance of infrastructure. The democratic process is the infrastructure of that infrastructure — one of the ways that we build the world we want to live in together. The power of a meaningful ballot is a measure of belonging. Talk to a voter who’s been unjustly excluded, or a voter newly enfranchised or re-enfranchised, and you feel it firsthand.

That the position exists — the first of its kind — and that it sits where it sits, speaks to the administration’s priorities. That it has to exist at all speaks to our environment.

Part of it is the toxic effort to profit from the nativist fiction that elections are being stolen from “real” Americans. But that’s hardly the only danger. Elections are chronically underfunded. Voting rules and districting authority have been weaponized against the public. The social determinants of democracy — the information we consume and the communities that help us maintain common humanity — are fraying.

It’s not all bad news. In recent years, we’ve gotten closer than ever to a roster of elected officials who accurately represent the country’s diversity. And in 2020, during a deadly pandemic, 67% of eligible Americans voted – more than at any point since the 19th Amendment doubled the national denominator. It’s the right trajectory. But for any professor, a grade of 67% still leaves plenty of room for improvement.

That’s the context I inherited, stepping into an impossibly capacious title. The White House doesn’t run democracy. You do. But with unflinching attention to the limits on presidential authority, and an equally keen sense of the scope of the challenge, we helped wherever we could.

There were unbeatable moments. Congress passed a bipartisan (!) statute limiting opportunities for misconduct in counting votes for president. For the first time ever, federal programs were designated by state officials (Republican and Democratic) as one-stop voter registration locations. The national budget committed to historic levels of sustained funding for elections. I had the chance to stand with the president as he announced a renewed call to national service, and to sit with the vice president as she welcomed a roundtable of poll workers. (“‘Poll worker’ is Levitt’s love language,” said one colleague. She’s absolutely right.)

There is still so, so much more to do. After 20 months, I’m back at the law school, as confident as ever in the dedication and skill of those who continue to serve, and doing my part to nurture those who will serve next. I’ve got one eye out for administration announcements that were still baking when I left. And one eye firmly on the rest of us, where even more work to keep our democracy gets done.

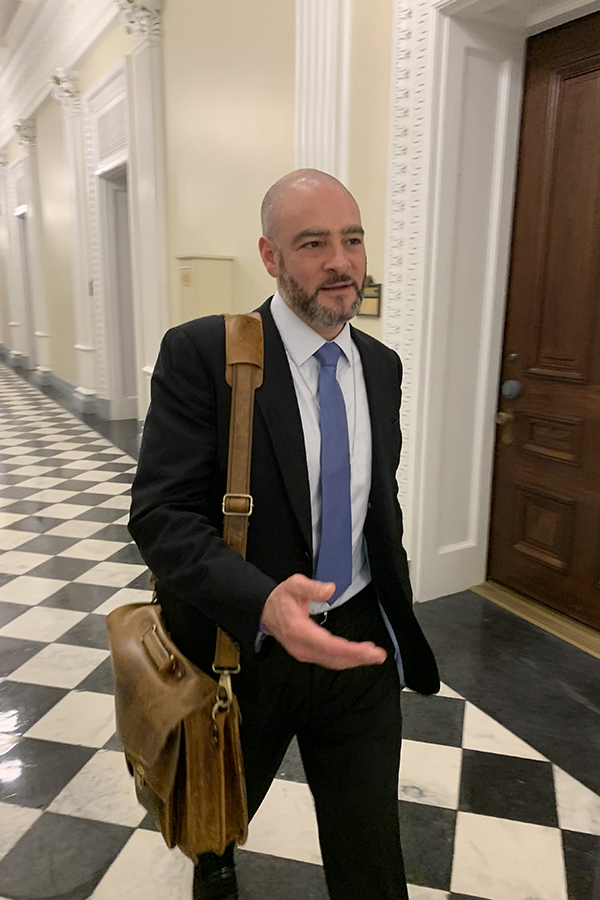

Justin Levitt is a professor of law and Gerald T. McLaughlin Fellow at LMU Loyola Law School. A nationally recognized scholar of constitutional law and the law of democracy, he served from 2021-22 as the White House’s first Senior Policy Advisor for Democracy and Voting Rights.