The geometric skull of Heart Mountain in Wyoming is quite distinct: it rises from a sprawling valley, as if it has been carved with a specific design in mind; its head, neither smooth, nor vast, is composed of limestone that is at least 250 million years older than the rocks at its base. It is said to have been formed during turbulent geologic times, and that Heart Mountain alone had traveled more than 65 miles away from the cluster of other mountains it was part of, because of a massive landslide caused by the eruption of the now extinct volcanoes of the Absaroka Range. It is beautiful to look at, really, whether it is painted or sketched, which is how it is often portrayed; still recognizable, still stunningly unique. Though it is filled with a more disturbing history too.

Sometime in the mid-1900s, a girl with a small demeanor and a big heart began collecting different items her and members of her family received, mostly invitations to the town’s various social affairs and gatherings. Among them were a Brown Derby Social, an invitation to a senior prom, various dance invitations, the Club 27 Farmer’s Ball, a Looking for Yesterday Social (that specifies for couples only), a menu from Club Chattanooga, and more. Every invitation seems to be handmade, adorned with long and narrow exquisite handwriting, sometimes showing up with a bold typeface on the cover, bubbling in bright blues, emerald greens, and colored-in silhouettes. The invitations have been folded elegantly, organized neatly, and glued into a scrapbook, so that if one were to open them, they would unfold slowly, their contents still intact, unraveling the joys and wonders of the lives they held. This meticulous collecting and organizing is clearly the work of someone who took the time to tell the story of her family and a more nuanced narrative of her community.

If one were to consider the scrapbook by itself, it may evoke feelings of nostalgia, of another time, of carefully curated memories of a community, filled with joy and quotidian details. Perhaps they were meant to be remembered that way, but the invitations are all gathered under the heading Dance Bids on the front page, though the cover is really what complicates the narrative further: the geometric skull of Heart Mountain is sketched carefully, its geographic morphology duplicated remarkably well, and beneath it, a barbed wire fence, with two armed soldiers standing on the outside. Inside, on the other side of the fence, overlooking the passive gaze of the mountain, are the roofs of different sheds, eerily similar to one another – all markers of the ghastly forced resettlement of a Japanese American community, and the makeshift of an “internment camp” like many others that appeared around the U.S. in the 1940s.

She didn’t know it then, but the girl, Agnes Ichikawa (nicknamed Tiny), was doing something quite radical: by collecting the invitations that her and her family received, she was choosing to preserve part of their history, according to her, thus determining a new narrative we wouldn’t otherwise have access to; a narrative that is important to remember, important to preserve.

Cynthia Becht, head of Archives and Special Collections at Loyola Marymount University’s William H. Hannon Library, explains the importance of choosing to preserve one’s narrative for future generations. “One of the toughest responsibilities for any special collections librarian or archivist is the decision-making regarding which archival collection, or which object, the institution chooses to save. When we think of saving, we’re talking about still being here, 100 or 200 years from now.” It’s a responsibility that doesn’t come lightly to Archives and Special Collections, and one the staff shares collaboratively and proactively with different partners across the institution.

One of the toughest responsibilities for any special collections librarian or archivist is the decision-making of which archival collection, or which object the institution chooses to save.

The department itself boasts a stunning collection of 12,000 volumes of rare books, including first editions of English and American literature, and early printed books including nine complete incunabula (books printed earlier than the 1500s). The library’s greatest print treasures include a First Folio of Shakespeare, and the 1481 Divine Comedy of Dante, illustrated by Botticelli. Archives and Special Collections also features more than 1 million postcards from around the world; various manuscript collections (including 1,500 linear feet of collections of California and Los Angeles history); audiovisual collections; art and artifacts (ranging from Japanese art to Baroque art to German Expressionism, and more). In recent years, the department has been making active efforts to include materials from marginalized communities, such as the Ichikawa Family Papers.

Everything the institution accepts to preserve and archive becomes part of the historical record that future generations will use to understand the past, making it a complicated and important decision.

For example, archiving the stories of marginalized communities that have been overlooked throughout history, or how they’ve been reframed and presented in a way that does not portray the perspective of lived experiences from the people of the same communities. “This is a decision that requires a truly collaborative effort” said Becht, when asked how the institution chooses which collections to preserve. “We work with partners across campus to make sure there is enough visibility and representation of voices that have been historically marginalized. It’s important to pay attention to the voices that have been silenced in the past, and to make sure we do our part, to bring narratives that are complex and true to the perspective of the communities that lived them.”

This is no easy task, but it is exactly how the library ended up with the Ichikawa Family Papers, a staggering collection that includes art, prints, artifacts, photographs, school and work material, scrapbooks, and other ephemera. The Ichikawas were a Japanese American family living in Los Angeles for most of the 20th century. After Executive Order 9066 was issued in 1942, the Ichikawas were forcibly detained and incarcerated at Heart Mountain Relocation Center, a Japanese American “internment camp,” until 1945.

The collection documents their lives in a way that is rich, multilayered, and intricate, a narrative that can be told and preserved only through their unique perspective, only through their eyes. It is a collection that stands as a testament to the family’s own resilience, to their endurance throughout their relocation, and to the ways they chose to bring a sense of normalcy to their lives. Amidst the trauma of being forcibly removed and resettled into a makeshift home, they found the strength to build a new community, to attend dance parties, to gather at clubs, to put together proms for their children, to live full, rich lives despite the turbulent circumstances ascribed to them.

It is specifically in times of deep trauma that people often find themselves doing works of community building, doing the important work of preservation. When the Arab Spring was in full rupture in Egypt in 2011, and Tahrir Square in Cairo was filled to the brim with protests, the acclaimed Egyptian Lebanese photographer, archivist, and multimedia artist Lara Baladi took it upon herself to create Vox Populi, an ongoing archival project that included a series of media initiatives, artworks, publications, and an open source timeline and portal into web-based archives, to document the 2011 Egyptian revolution and other global social movements at the time. This kind of intentional archival work goes beyond mere documenting of the lives of our communities; it enables us to collect and preserve original and authentic materials that, combined, can help construct a narrative that may otherwise be distorted, silenced, or ignored. Beyond the mere act of collection, archival work also becomes an act of defiance, an act of resistance and survival, an act of social activism, upon which we can imprint our historical significance. This work allows us to impart important and accurate depictions of our communities for future generations, where our voices are represented, collectively and individually, in a way that is unmistakably ours.

Beyond the mere act of collection, archival work also becomes an act of defiance, an act of resistance and survival, an act of social activism, one upon which we can imprint our historical significance.

Recently, when Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was unfolding, the critically acclaimed writer and poet Ilya Kaminsky, who was born in the former Soviet Union occupied Odessa (Ukraine), began suddenly and frantically sharing updates with his followers. At the time, he was looking for his uncle, whom he was not able to locate, and his tweets provided almost hourly updates of his continued efforts, documenting thoroughly the responses he received from different members of his community living in the country, who all found themselves at the cusp of a new war overnight. It was an authentic portrayal of what was happening at the time, and how people were responding to the war. At one point, he emailed a friend in Ukraine asking if there was anything he could do; the friend replied and asked if he could send him poems – they were working on a literary journal, and they needed good poems. The remarkable work of collecting and archiving requires us to see beyond our immediate moment of trauma, that we hold in our imagining the possibility of better days to come, and in anticipation of that, can see ourselves making an impact through our work, through our art and artifacts, through our daily lives. In this instance, and in the instance of the Ichikawas, living in itself, surviving by living a life that was anything but ordinary, is the act of perseverance, an act that informs future generations, an act that opens their eyes to more voices, to understanding the cultural and historical significance of marginalized communities through their preserved works.

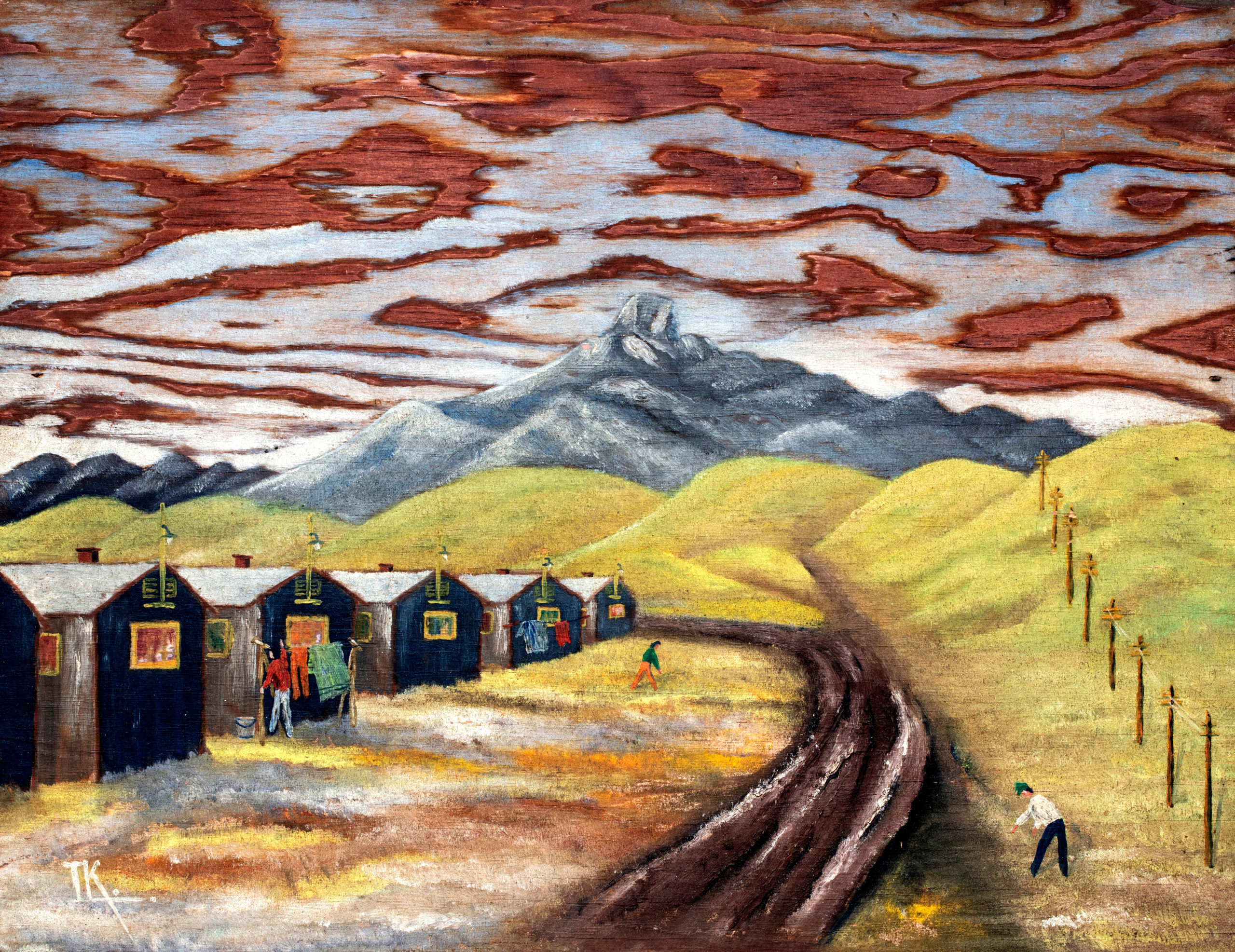

In the collection of the Ichikawa Family Papers, there is a painting by an unknown artist. The painting depicts a gray sky with maroon clouds, and towering above it, the squared head of Heart Mountain standing translucent; not too far away are five sheds that all look exactly the same. The only people depicted in the artwork are all looking away and working, all on the other side of the fence. It’s a desolate landscape depicting the devastating reality of its inhabitants, and one the Ichikawa Family chose to keep as a memento when they resettled back in their Los Angeles home, a reminder of the fraught home they had built in Heart Mountain.

In the past, this kind of artwork would have been catalogued with less-inclusive language; but part of preserving and archiving the histories of marginalized communities also requires a particular attention to the language used to describe and depict such histories. “Language can be misleading,” said LMU Processing Archivist Marisa Ramirez, referring to the type of language that has been used in the past to describe the collections of marginalized communities. “Because of this, it is important to include members of the communities whose collections we have, to help us understand their own narratives. It’s a way to have their voices heard, and to reaffirm the significance of their stories as well.”

This kind of remarkable work of collecting and archiving requires that we see beyond our immediate moment of trauma, that we hold in our imagining the possibility of better days to come in the near future.

This is the impetus behind some of the most compelling projects Archives and Special Collections has taken on in recent years, including the Venegas Family Papers, the Robert Singleton Papers, the J.D. Black Papers, and more. The Inclusive History and Images Project (IHIP), for example, reflects this active effort to include the voices of the communities in the collection itself; the project is an important component of LMU’s ongoing, university-wide anti-racism initiative that seeks to address important gaps in understanding its own institutional history by gathering stories and images from alumni and the greater LMU community to tell the full and inclusive story of LMU.

An important part of collection and archival work is also finding different ways students can engage with such collections in a way that is meaningful and creates critical inquiry. During the last academic year, Archives and Special Collections hosted more than 80 class sessions, ranging from English, Art History, African American Studies, Theater Arts, Urban Studies, Women’s Studies, and Theology, as well as First Year Seminars and Rhetorical Arts.

When the rhetoric art class of Laura Poladian, a Rhetorical Arts Fellow and writing instructor, met with Archives and Special Collections librarian Rachel Wen-Paloutzian during the pandemic, they set for themselves a lofty goal: to tell stories through unique archival materials. The students were instrumental in creating digital archives of the Venegas Family Papers. The students also had the opportunity to meet virtually with members of the family, an experience that supplemented the rich digital collection. “At the time, the students themselves took on the role of becoming archivists, because they were hearing new stories from the Venegas family members, and documenting the oral narratives in such creative ways,” said Wen-Paloutzian, who leads classroom instruction and is tasked with making sure that students continue to have an active engagement with the collections. “It was interesting to see the transformation happen, to see students being interested so much in the narratives they were exploring, and what they were able to bring to such an enriching conversation and experience,” she added.

What makes archival work so powerful is that it never really remains stagnant; though it is meant to be preserved, untarnished, and untainted, it is also meant to be interacted with. It is meant to create engagement between faculty and students, to be thought-provoking, to teach students to question the narratives that are presented to them, and to teach them how to be good scholars.

It is exactly for this purpose that Archives and Special Collections has a unique, hands-on approach that encourages students to engage and examine the collections; through classes, seminars, events, and student-curated exhibitions, it encourages a kind of experiential learning that is rare, and one that will certainly have a long-lasting impact on students.

Heart Mountain, by itself, may be the reminder of a marred history; however, when its artwork was incorporated as part of the Ichikawa family’s history, its narrative was effectively shifted, as have the trajectories of the family’s life. Simply by including Heart Mountain in their collection, the Ichikawas have done something quite remarkable: they have taken ownership of their own narrative, and, by doing so, they have repurposed the significance of the mountain itself; what may have been considered an image of strife and trauma, has now become a symbol of the family’s perseverance, of their strength, of their will to survive and thrive.

It is an astonishing testament of what archival work can do when the communities themselves are allowed to tell their own stories; it becomes more than an instrument of storytelling, it becomes a way to weave our narratives with those of others, a way to inspire others to engage further, and more intentionally, with such materials and collections.

Learn more about the William H. Hannon Library’s Department of Archives and Special Collections.