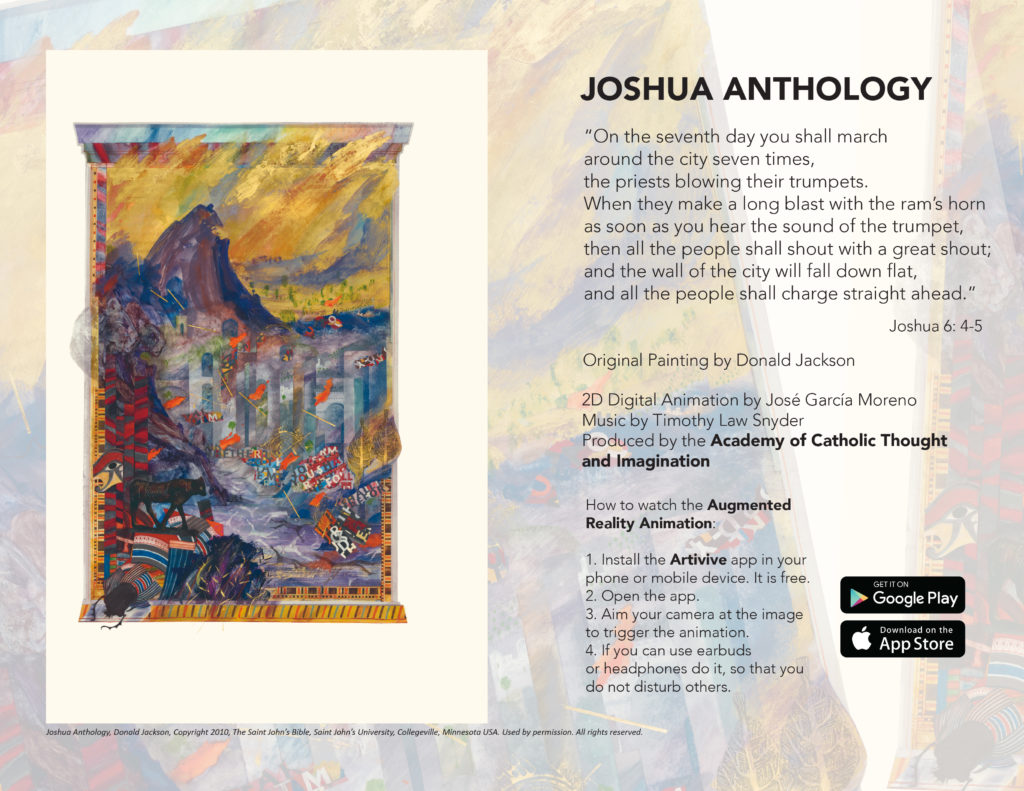

Imagine this: skies with strokes of bright yellow and splashes of orange, as if they’re turning into flames. Below them, a mountain with a gaping wound, looking upon its valley, filled with scattered trees, scattered people. Some have been marked by numbers and letters; others have turned into faint silhouettes. Beneath the mountain, worlds have unfolded; flames are everywhere, golden lances that seem to have descended from the bulging skies. A black ox, also adorned in gold, is looking on; a solitary eye lurks behind it. The city walls seem to be crumbling, with more people scattered on the ground.

Though there are many more details to consider, what stands out most is the combination of iridescent colors and somber hues, which seem to tell different stories at the same time. This is Donald Jackson’s painting “Joshua Anthology,” commissioned for St. John’s Bible, an image that is both still, and dynamic, and certainly lends itself to being digitally animated.

This is exactly what José García Moreno, director of Loyola Marymount University’s Academy of Catholic Thought and Imagination (ACTI) was inspired to do when he first saw it; he was left with a new sense of wonder, of awe, and it catapulted his artistic mind to imagine what else it could become, what other layers he could add to it that would make the experience of encountering the artwork itself memorable. “I am always thinking about the sacramentality of the arts and sciences,” he said. “These aspects that are not really thought about as part of the discussion of what is the meaning of Catholic thought and imagination, that was really important for me to bring to ACTI.”

He was left with a new sense of wonder, of awe, and it catapulted his artistic mind to imagine what else it could become, what other layers he could add to it that would make the experience of encountering the artwork itself memorable.

ACTI is a community of scholars who work in dialogue with the Catholic intellectual tradition by developing, critically examining, communicating or otherwise engaging the rich resources of Catholic thought and imagination, especially as it is informed by Ignatian vision. Since its inception, ACTI has served as a hub for scholarship, interdisciplinary research, innovative pedagogy, and creative outreach across LMU and beyond.

García Moreno is a celebrated artist, a filmmaker, a digital animator, and a visionary (he was named the winner of the 2021 Collegium Visionary Award, presented by a consortium of 65 Catholic colleges and universities in the U.S. and Canada). His work has always been forward-thinking, and difficult to conceptualize in the early stages. He relishes in that difficulty, because it means he’s working toward something that’s never been done before, something meaningful and boundary-pushing.

This is the kind of thinking he brought when he first joined ACTI in 2020, and when this spring he put together “Icon Animorum,” a fully immersive experiential exhibit of the St. John’s Bible at LMU’s William H. Hannon Library, which possesses the heritage edition of the work. “I am always asking how technology can play a part in the evolution of spirituality,” he said.

Consider the recently released images by the James Webb Space Telescope; the First Deep Field image captured thousands of galaxies flooding in the cluster SMACS 0723. It would be impossible to attempt to describe what the telescope was able to capture without the image itself, the deepest and sharpest infrared image of the distant universe to date.

Yet, even with this groundbreaking technology, we are left speechless, struck at such vastness, such intricate beauty that shapes the progress of our universe; even with the set of images that were released afterward, we are still left with a buoying sense of the unknown – how, even we, in all our knowledge, wisdom, technological, and scientific advancements, are just beginning to uncover the mysteries of the world we live in.

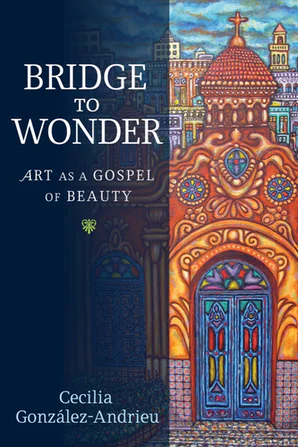

This sense of wonder and awe is what Cecilia González-Andrieu, professor of theology and theological aesthetics, a theology ethicist, and a self-described feminist Latina, talks about in her work. In her book, “Bridge to Wonder: Art as a Gospel of Beauty,” she lays out the groundwork for how art can be used to provide a glimpse into the ineffable, into what is the unknown, or that which couldn’t be described in mere words. It’s the same sense of wonder we get when we experience art across different disciplines; it arrests us where we are, it moves us, and we are left transformed by it (though we may not be able to articulate how). It’s experiencing something transcendent, something beyond ourselves that brings more significance to our existence, that renews our purpose, and reinvigorates our passions. “While no human experience can disclose what the mystery of God is,” González-Andrieu said, “experiences that brim with beauty … can suddenly make us aware of the enticing mystery enveloping us.”

It’s the same sense of wonder we get when we experience art across different disciplines; it arrests us where we are, it moves us, and we are left transformed by it.

González-Andrieu specializes in analyzing art from the perspective of theological aesthetics, an interdisciplinary field that looks closely at how artistic beauty is embedded with a revelatory and prophetic power that goes beyond the self to the communal. She was the recipient of a fellowship from ACTI, which allows faculty to complete research or a creative project that aligns with the center’s mission. Her project asked how one engages with the arts in a way that expands our understanding of the wonders of the world. When González-Andrieu explains the field, she is careful not to forget how the academic discourse of the arts and sciences may have excluded the work of marginalized communities in the past; she said she is intentional about her approach, and she works to expand the field through her own experience and identity, bringing a particular viewpoint of aesthetics that considers beauty.

She poses as an example the work of John August Swanson, a longtime friend of LMU who attended Loyola Marymount University in the 1950s, and a prolific artist whose work addresses human values, cultural roots, and the quest for self-discovery through visual images. García Moreno and González-Andrieu are collaborating on a project that will feature August Swanson’s work in a series of short, animated films. González-Andrieu discusses the example of his limited-edition serigraph, “The Last Supper,” which she compares to Leonardo da Vinci’s artwork with the same title.

Although both pieces of art depict the same scene, they are wildly different portrayals. Da Vinci’s painting is marked by a long, rectangular table, where all the apostles are lined up (with Jesus in the center). The color palette used is quite pale; the apostles seem to be huddled in groups of two or three, their expressions that of surprise or indignation. There aren’t any elements that would make us believe that this gathering was warm or communal. August Swanson’s, on the other hand, is filled with bright colors, the table is round, indicating a more communal element of the gathering, the wine shared is similar in color to the other elements included in the scene, and, most notoriously, Judas, who eventually betrays Jesus, does not stand out. It’s a more egalitarian look, one that takes into consideration the community of the apostles first, without necessarily neglecting the threat of the betrayal that was to follow.

One cannot help but experience beauty when encountering the serigraph, but more than that, González-Andrieu brings her sharp eye to what the art included at the edges of the serigraph itself, depicting all the people who contributed to the scene one way or another. “It is an invitation,” she said, “for us to engage with the art in a way that makes it possible to really access it with all its richness, its nuances, and complexities.”

Paul Harris, professor of English, is no stranger to experiencing art that is both pervasive and eye-opening. Harris, who was also a recipient of the ACTI fellowship, talks about the marrying of arts and sciences in a way that seems wholly instrumental to our existence. “How does one look at the images released by the James Webb Space Telescope, and not be inspired to write poetry? How can one attempt to produce art, and not implement a scientifical approach,” he asked.

Harris has an interest in a range of disciplines, including literature and science, chaos/complexity theory, literary theory, neuroscience, architecture, constraint-based writing, the interdisciplinary study of time, and more. Most recently, he has been enthralled by the notion of the petriverse, a term used to denote both a world composed of rocks (such as a rock garden), and words composed of rocks.

“It’s a way to ground yourself in time, to have a reflective place,” said Harris, who has also helped shape The Garden of Slow-Time at LMU. His proposed project for ACTI, “The Composition of Place-Time,” looked at the dynamic relation to space, and a temporal or historical understanding of place. “When we walk, we feel all of our ancestors behind us,” he said, “And we think of the generations to come. The composition of place-time is really about feeling the history of a place, not just human history, but geologic history too.” This makes us both small and significant at the same time; “I am always asking, are we being good ancestors today?” he added.

The element of wonder comes at each stage of García Moreno’s work, whether he’s working as a digital animator, as a filmmaker, as an artist, or as an administrator. With interfaith and interdisciplinary dialogue being so central to ACTI, García Moreno found himself pondering how he could help further elevate that sense of wonder. He asked himself, what else could technology do that it hasn’t done before? How could he, for example, use digital animation to advance narratives meant to be experienced differently?

This line of thinking is what lead him to “Icon Animorum,” which included a panel of artists, writers, scholars, and thinkers from different faiths and disciplines. “I think that art is a way of bringing forward ideas, sensations, or thoughts that cannot just be accomplished with words and logical thinking, so it’s more experiential in nature,” García Moreno said.

I think that art is a way of bringing forward ideas, sensations, or thoughts that cannot just be accomplished with words and logical thinking, so it’s more experiential in nature.

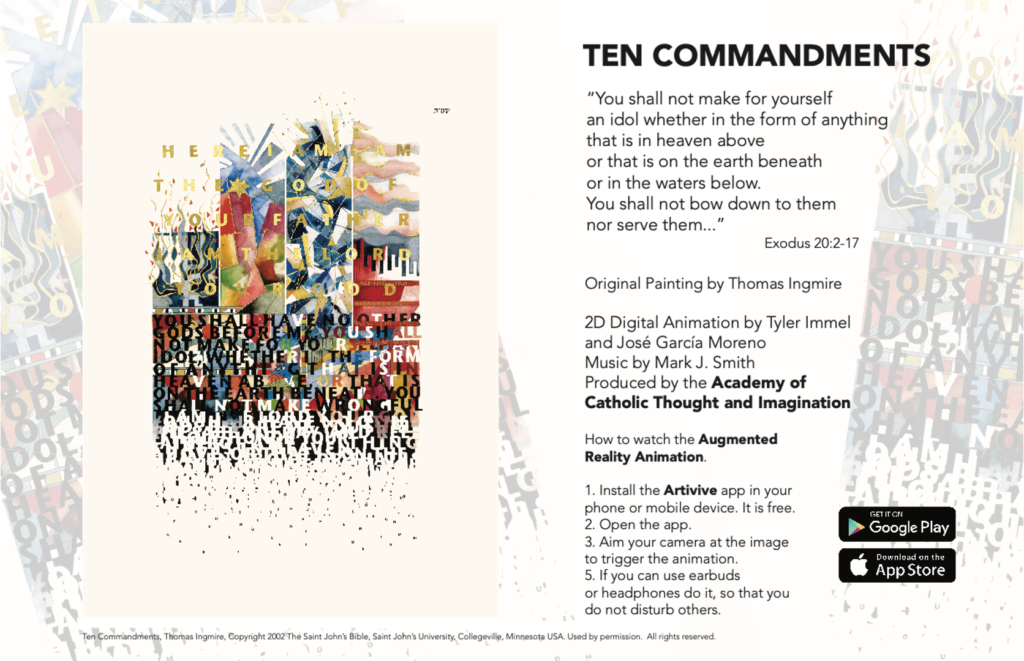

García Moreno took his vision, and transformed it into a fully immersive experience, which included a 3D printed mutoscope (an early motion picture device invented in the 1800’s) through which a series of action sequences were projected; selected passages such as Ecclesiastes, The Woman and the Dragon, and the Ten Commandments were fully animated, and several stop-motion animated pieces transformed the experience of the show.

Directed by José García Moreno

Augmented Reality Animation by José García Moreno

Original Music by Timothy Law Snyder

Produced by José García Moreno and ACTI

Copyright 2022. All rights reserved.

Exhibited at “Icon Animorum” , William H. Hannon Library, Los Angeles, California, March-April 2022

Original Painting by Donald Jackson

Joshua Anthology, Donald Jackson, Copyright 2010, The Saint John’s Bible, Saint John’s University, Collegeville, Minnesota USA. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Directed by José García Moreno

Augmented Reality Animation by Amy Wong, Andy Cepollina, and José García Moreno

Original Music by Ryan Steele

Produced by José García Moreno and ACTI

Copyright 2022. All rights reserved.

Exhibited at “Icon Animorum”, William H. Hannon Library, Los Angeles, California, March-April 2022

Original Painting by Donald Jackson

Woman and the Dragon, Donald Jackson, Copyright 2011, The Saint John’s Bible, Saint John’s University, Collegeville, Minnesota USA. Used by permission. All rights reserved. The Cosmic Battle, Donald Jackson, Copyright 2011, The Saint John’s Bible, Saint John’s University, Collegeville, Minnesota USA. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

This is the kind of show that relies on its audience’s participatory role to succeed; each person is not simply expected to be the passive observer of the work. Instead, we are invited to take action, to use our phones to experience the music and animation, to listen to interdisciplinary dialogue that frames the entire show, and, most importantly, to take the leap, and use our imagination as a way of bridging the gap between what is seen and unseen, between what we are experiencing immediately, and what will linger with us afterward. The show relied on collaborators across disciplines and fields to come together, people who all shared the vision of García Moreno’s own thinking, who thought of the future as being interdisciplinary.

John Sebastian, vice president of Mission and Ministry, said he was excited to see the kind of worldview that García Moreno brought when he joined ACTI. “José’s work is highly interdisciplinary,” he said, “connected around this commitment to looking at not just how theology asks questions, or how philosophy asks questions, but how we can really bring those traditional disciplines together with the arts, together with science and technology, to really generate some interesting questions.”

Beyond the exhibit, this is really what shaped the scope and mission of the center, which is being reimagined as The Center for Spirituality and Technology, focusing on interdisciplinary work. The center will continue to provide a space that is new, necessary, and immediate, serving as a connector not just between different disciplines, but also between different generations, imaginations, backgrounds, worldviews, faiths, and cultures.

It’s the type of work that attempts to bring together people from different backgrounds, embracing their uniqueness and individuality, and one that attempts to also curate experiences and produce scholarship that will lead to a more universal experience: that of experiencing beauty and wonder.