“Can you tell me what tomorrow is, Hanun?” asks Teacher Mike, raising one eyebrow at the boy to indicate he had seen him fooling around with another classmate moments before.

“Remembrance Day!” he replies.

“And what is it that we’re remembering?”

“The Khmer Rouge,” they all say, “the Khmer Rouge!”

“And are we happy? Are we celebrating them by remembering them? Were the Khmer Rouge good people?”

A chorus of dissent and hissing follows.

Such was the scene in Mike Norman’s fifth-grade classroom the day before Remembrance Day at New Hope for Cambodian Children. He is one of several Westerners who teaches at the school and orphanage dedicated to the care and education of Cambodian orphans, many of whom also deal with HIV. The center, founded by Americans John and Kathy Tucker and the largest of its kind in Cambodia, gives the children a home free of approbation and poverty surrounding them. What the center cannot guarantee is freedom from Cambodia’s past–in fact, these children are products of it and form a crucial part of the popular memory surrounding it.

On my recent trip to Cambodia with Ignacio Companions, I became aware of just how much the past can affect the present. Studying history at LMU has exposed me to it before, but this trip solidified the power and pervasiveness of public history and memory.

As we boarded a bus from the airport in Phnom Penh, we were told that most everyone we would meet had some personal or familial story about the Khmer Rouge, and had been affected by the genocide which took over two million Cambodian lives.

While mostly working at New Hope as teacher’s assistants, my group got the chance to visit two of the most prominent sites of memory in Cambodia. The first was the Tuol Sleng prison, or S-21, in Phnom Penh. It was initially a high school before its transformation into a place of torture and murder during the communist takeover. The second was the striking national monument at the Killing Fields.

S-21 was part of a network of over 100 imprisonment sites organized hastily by the Khmer Rouge after their 1975 ousting of the American-supported Khmer Republic. The communist forces famously marched all Cambodians from the city without exemption for the old or the infirm. They killed academics, intellectuals, professionals, members of the middle class, and anyone else they deemed to be “new people” who corrupted their idea of the Cambodian-peasant-farmer spirit. Pol Pot, the leader of the Khmer Rouge, forcibly wrought a new society–illiterate, impoverished, and utterly dependent upon the Khmer Rouge for survival.

A survivor of the atrocities that took place within the walls of S-21 narrated the audio tour. He describes it as a “place of nightmares” through which thousands were brought but few survived. “After you visit, you, too, will be a keeper of memory,” he says.

“There are no diplomas, only diplomas one can visualize. If you wish to get a Baccalaureate, you have to get it at dams and canals.”

Khmer Rouge propaganda

It is true. Room after room has remained untouched since the conquering Vietnamese troops arrived after the regime’s collapse. Most contain a rusty bed frame with shackles, a simple desk (for writing out forced confessions) and a munitions box for human waste.

Above the beds are framed photos taken by a Vietnamese army photographer on the day of the prison’s liberation. Several depict the corpses of those killed by the fanatical troops of Pol Pot towards the end of communist control. Most were not shot, but rather bludgeoned or cut to death, to avoid the loud reports of rifles that might bring the oncoming troops closer.

“One hand for production, one hand for striking the enemy.”

Khmer Rouge propaganda

As I made my way through the museum, artifacts and images from the rise of the Khmer Rouge intermingled with the audio clips. The place is mostly filled with tourists, and a booth outside asks for donations because many Cambodian schoolchildren cannot afford the entrance fee.

S-21 was in disuse when it reopened to the public in 1980 and was not a museum at that time by the popular understanding of the term. A faded sign on the third floor reports that until the mid-2000s S-21 lacked a “thorough educational dimension.” It was not a site of public memory yet, but rather a grim reminder of a dark time with which few interfaced. The prison is now as a site of cultural importance and features in its final courtyard a monument to the victims of the genocide. The audio tour concluded with a clip from a speech of the German ambassador to Cambodia at the monument’s dedication:

“Recovering, forging a new future,” he says, is a matter of dealing with “national trauma” in such a way that excuses nothing of the past and demands a constant and vigilant reconsideration of its telling.

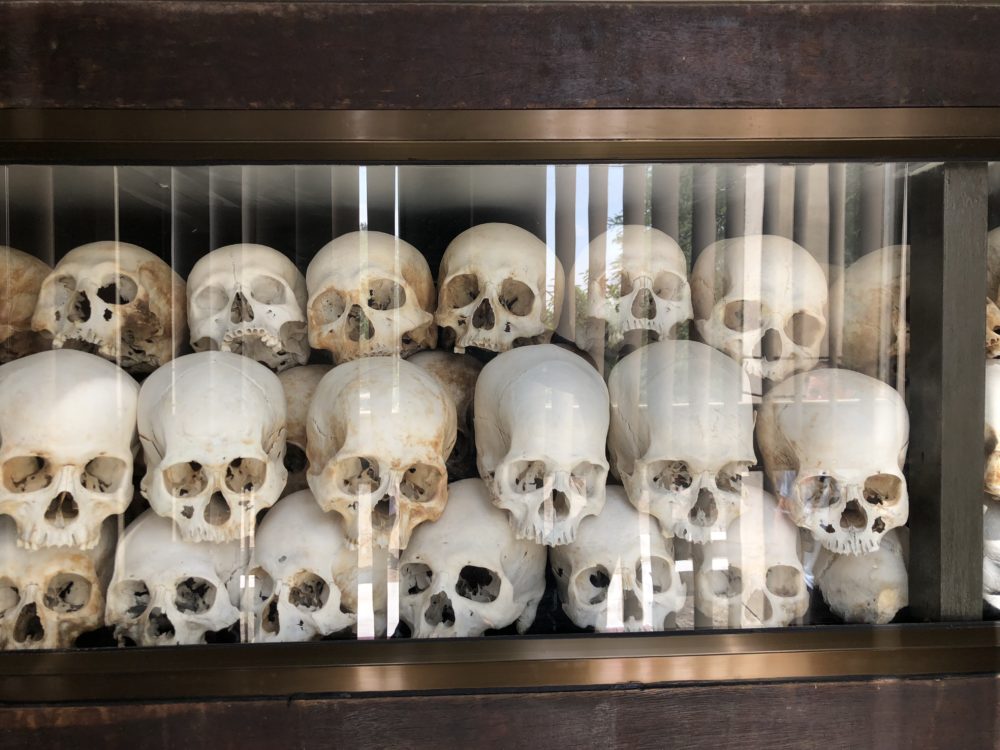

At the Killing Fields, a dusty drive out into the countryside leads to a temple-like structure surrounded by lush jungle, and there is a different feeling. This is the visceral part of the trip.

“The Bureaucracy of Death distances perpetrators from total responsibility…”

Helen Jarvis, Australian historian of the Cambodian Genocide

While the prison was emotionally difficult to process, this was an actual site of genocide. It is overwhelming to walk about the grounds and see so much of the brutality still present. Shreds of clothes are half-buried in the dirt and large pits are cordoned off because there are still remains in them. The audio tour points out a marked tree, explaining that babies were smashed against the trunk. Another marked pit was primarily for the elderly and the children who were brought there. The cruelty of the place is evident and devastating.

Cambodia’s tragic past is more raw, more recent, and closer to home. Everyday people living and working throughout Cambodia, if they are over the age of twenty-five, have memories of Khmer Rouge terrorism in the nineties and if they are any older probably the regime’s crimes themselves. Pol Pot’s government–recognized by most Western nations–killed or otherwise neutralized every possible opposition and forced those deemed acceptable into failing collective farms and doomed work projects to create a communist agrarian utopia.

The one thing that sticks out as we drive away, past the rows of coffee shops and cafes that crowd the road, is that here in Cambodia everyday life continues and must continue. For the vast majority of its citizens, Cambodian history is unreconstructed but very, very close.

History major Nishan Silva is a rising senior.