LMU Loyola Law School (LLS) has been honored with a gift of $400,000 in support of its cutting-edge suite of programs encouraging law students to pursue work in civil rights — a challenging field to enter, as clients typically cannot pay much and cases can take years, even decades, to settle. The thoughtful gift comes from the Utah Civil Rights and Liberties Foundation, a nonprofit founded by the late LLS alumnus Brian Barnard, J.D. ’69.

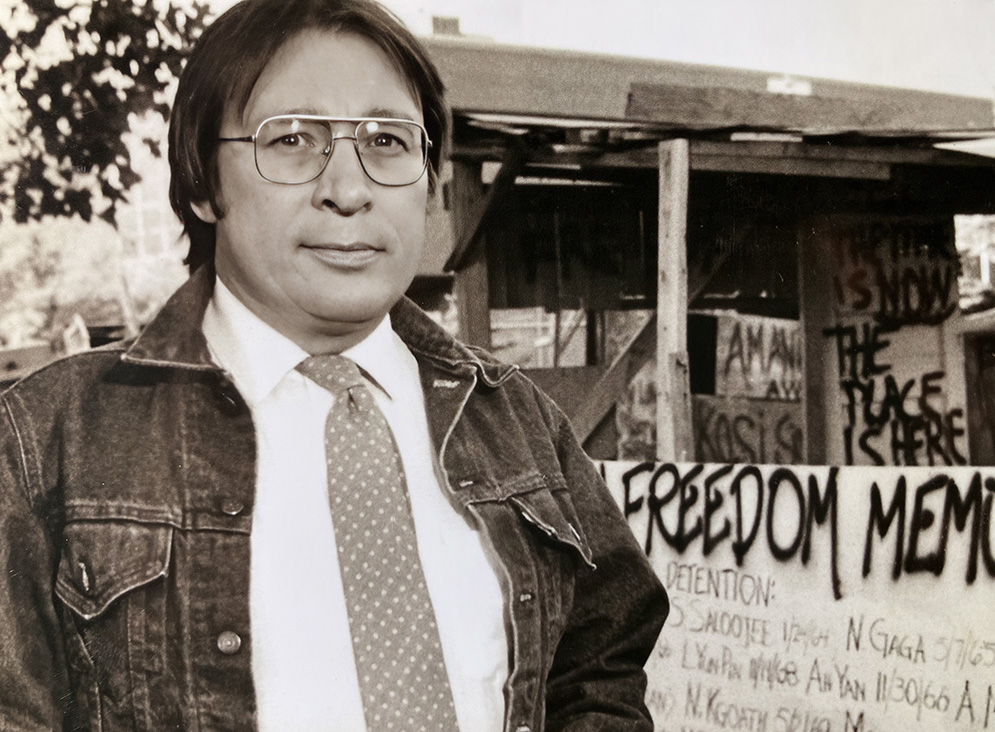

During his lifetime, Barnard was deeply committed to the practice of civil rights law. Taking immense pride in fighting for people who did not have the resources to fight for themselves, Barnard’s clients included prisoners, unhoused individuals, victims of police brutality, women experiencing gender discrimination, and practitioners of alternative religions, among many other constituents. Known as a warm and giving individual, Barnard was beloved both by the people he worked with and the people he advocated for. The Salt Lake City, Utah, community where he had set up his practice in the early 1970s held him up as a hero: People often stopped him on the street to cheer on his good work.

In 1984, Barnard established the Utah Civil Rights and Liberties Foundation as a means of providing additional financial support for his civil rights cases. For many years, the foundation’s resources were modest, but in 2010, Barnard and his Utah Legal Clinic finally saw the fruition of an 18-year battle between the State of Utah and the Navajo Nation over unpaid oil drilling royalties. With his share of a $33 million settlement, Barnard was able to make the largest investment to date in the foundation. Before he could reap the full benefit of those funds, however, the beloved attorney passed away in 2012.

The remaining staff at Utah Legal Clinic and the foundation’s board members did their best to carry on after his death. They soon affirmed, however, just how extraordinary Barnard’s commitment to his work was; because of the scant financial incentives, it proved difficult to find experienced attorneys who could take on civil rights work. In the past year, the small, close-knit collective of colleagues who had been a surrogate family to the childless lawyer made the decision, in consultation with Barnard’s relatives, to shut down both the clinic and the foundation, and to redistribute the remaining assets as grants. LMU Loyola Law School was among the first grant candidates to come to mind.

“Brian talked about LLS all the time,” said Heather Joosten, who sits on the board of the Utah Civil Rights and Liberties Foundation and worked alongside Barnard for many years as a paralegal. “He even ordered an LLS clock for his office. That school is where he found his love of civil rights — it shaped who he was.”

An LLS scholarship was set up in 2013 in Barnard’s name by his brother, John Perry Barnard, according to the late attorney’s wishes. The foundation decided to add more funds to this scholarship and to contribute to summer stipends for students working in civil rights, a fellowship for new graduates who wish to work in civil rights, and a one-year course in civil rights litigation that includes placement at a public interest organization or a law firm specializing in civil rights. Together, these programs are designed to provide much-needed assistance to students who want to work in civil rights — Barnard’s lifelong passion.

“This level of support is critical for students who aspire to pursue a path like Brian Barnard’s,” says Sande Buhai, J.D. ’82, director of the LLS Public Interest Law Department. “Those first jobs are always difficult due to a lack of funding. Our programs help students get their foot in the door, and hopefully from there, they go on to a full career in public interest. The programs have been in place for over 20 years now, and I am happy to see them get a boost of support from an inspiring alum like Brian.”

Gary Williams, the Johnnie L. Cochran, Jr. Chair in Civil Rights, teaches LLS’ one-year course in civil rights litigation, which Buhai lauds as “the best in the nation, cutting-edge.” About 20 students take the class each year, spending the fall semester in the classroom and the spring semester working at nonprofits like the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), Asian Americans Advancing Justice (AAJC), Bet Tzedek Legal Services, or law firms that specialize in civil rights, such as Carol Sobel in Santa Monica. Issues they work on can include homelessness, free speech, immigration, wrongful convictions, transgender rights, and disability rights.

“It’s not easy doing civil rights work,” says Williams. “This is why we have to do everything we can to provide a supportive framework. I’m always gratified when I see students go to work at civil rights law firms or public interest nonprofits because those places are usually reluctant to hire new graduates, and the students tell me that it was my class that made the difference. Receiving this targeted support from the Utah Civil Rights and Liberties Foundation means that more students will be able to make that leap.”

Heather Rando, a niece of Barnard who also sits on the board of the Utah Civil Rights and Liberties Foundation, likens the grant to “a final gift” from her uncle. “I am so pleased that we can support LMU Loyola Law School’s civil rights programs,” she says. “The Utah Legal Clinic would have been delighted, for example, to have subsidized summer interns like the ones LLS can provide. While I am sad to bring the clinic and the foundation to an end, I am happy that we can transfer their resources to LLS. I can’t think of a better way to continue my uncle’s legacy.”

If you’d like to help LMU Loyola Law School propel the civil rights lawyers of tomorrow, you can make a gift here, or contact Kaitlyn Plummer, senior director of development, LMU Loyola Law School, at kaitlyn.plummer@lmu.edu or 310.338.4237.