“Uplifting Tales and Eroded Histories,” an interactive exhibit featuring works across various media, invites both speculation and contemplation of the Palos Verdes Peninsula’s geo-history.

“This exhibition has allowed me to indulge in my two favorite pastimes: playing with rocks and playing with words,” said Paul Harris, professor of English in the LMU Bellarmine College of Liberal Arts. In addition to Harris, the show features the work of artists Richard Turner and Michael Davis.

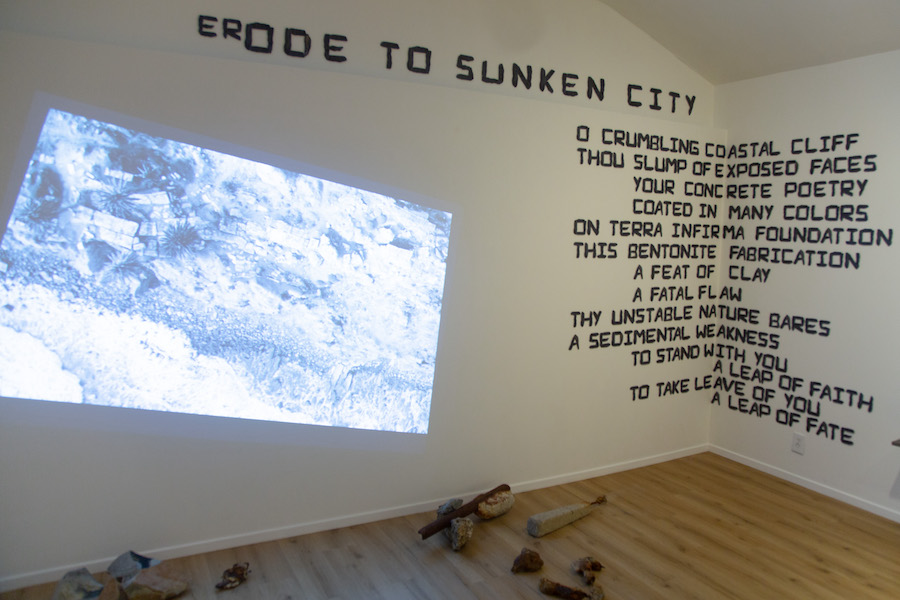

Visitors enter a gallery that is deliberately designed to be disorientating and reflective of the peninsula’s dynamic landscape. Drone footage swoops, dives, and plunges through “Sunken City” in the Point Fermin area of San Pedro. In 1929, a landslide sent several homes tumbling into the ocean and the remnants of foundations, curbsides, and piping from these homes remain; they have morphed into a forbidden, fenced-off hangout for thrill-seekers, graffiti artists, and rockhounders like Harris.

Harris fell in love with stones on the Palos Verdes Peninsula, a love that continues to inspire and inform his research, artwork, and writings. In 2000, Harris and his wife-to-be visited Abalone Cove and spent hours delighting in the dazzling array of pebbles and patterned fingers of rock formations. “That day was a profound experience of wonder: a visceral sensation that shocks your whole system; a feeling in your bones, body, and brain all at once,” said Harris. “In retrospect, I have come to realize that as I was being absorbed by the beauty of rocks, I was also absorbing the energy of stone, and by extension, the Earth.”

Since then, Palos Verdes, as well as Sunken City, White Point, and Cabrillo Beach in San Pedro, have become favorite pebble-fishing spots for Harris. In Harris’ “erOde to Sunken City,” which accompanies the drone footage in the first gallery of the exhibit, corner-turning text, epic tone, and geologic wordplay combine to channel the energy of and pay homage to Sunken City. Harris aptly describes Sunken City as “cautionary geologic tale, graffiti artwork, and ritual party site.”

In Harris’ “The Writing Is on the Wall” words again take shape, reminding us of the consequences of building structures and cities on faulty ground. That idea is reinforced by artist/curator Richard Turner’s mid-century models of single family homes, office buildings, and apartment buildings precariously perched on slanting shelves below Harris’ cracked concrete poetry. Together, “The Writing Is on the Wall” and Turner’s “Time Shore” work as a disaster thriller of sorts, depicting both the dangers and beauty of life on the edge.

San Pedro artist Michael Davis’ installation “ReCollections” combines a large 3D image of the San Pedro White Point recumbent fold – a type of geologic folding of sedimentary rock – with a series of “Jump Cuts,” digital images cleverly paired to paint a picture of how rocks have and continue to impact our consciousness.

The second room of the exhibit is a sharp contrast to the first: It seeks to evoke contemplative calm, through rock study and sitting with stones. In the “Stone on Stools” display Harris intertwines personal and geologic history by pairing rocks that he has collected with stools that his mother, Paula Trepanier Harris, collected as an antique dealer in Vermont. Viewers are invited to sit on 19th century Windsor thumb back chairs and marvel at how the earth made stones and manmade stools look like they belong together, while ruminating on the comparison between the deep-time journeys of stone and our short-lived moment on the planet.

“This is a beautiful project; breathtaking and awe inspiring,” said Dean Robbin D. Crabtree of LMU BCLA. “It is a blessing and a tonic to slow down and appreciate the beauty in the passage of time as seen in the life of stones and landscapes, and as captured by the images, objects, words, and arrangements in this immersive experience. The exhibit also depicts and evokes the forces of wear and tear, the erosion our natural environment and entropy of familiar inhabited spaces.”

Harris also incorporates geo-philosophical books and bookspine poems into the exhibit, both of which he uses to inspire inquiry and creativity in students who are fortunate enough to take his courses at LMU.

“Professor Harris’ work illustrates so many of the values and commitments we have here at LMU: collaboration, interdisciplinarity, education and action ‘off the Bluff,’ and the interplay of liberal arts disciplines, concepts, and methods,” said Dean Crabtree.

Another LMU connection can be found in his “Stone Stump Timestamp,” where he calls attention to ring patterns and timelines in nature. Stones with rings are displayed with a tree stump, which Harris and LMU Facilities Management salvaged from a fallen tree near Sacred Heart Chapel. Harris pointed out that the tree had church bells ringing through it, too.

“As an academic becoming an artist relatively late in life, I am deeply grateful to have had this opportunity,” said Harris. “I have learned so much about making art and what art can and should do.”

Harris currently has rock art on display in the Hannon Library exhibit (3rd floor atrium), Gail Wronsky Re-Written in Stone, pairing lines of Wronsky’s poetry with stone displays.