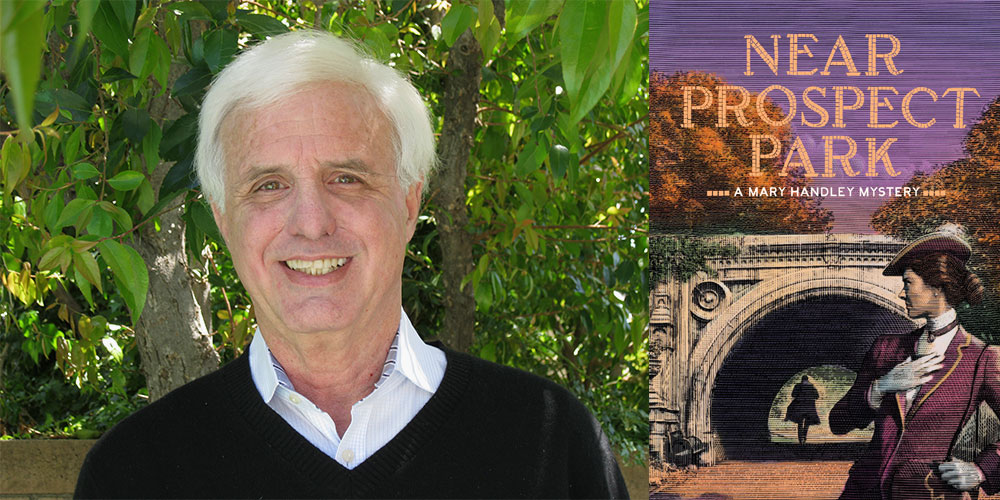

Lawrence H. Levy’s new novel reads like today’s all-too-familiar headlines, except this case isn’t recent—it’s from the Gilded Age. The fourth installment in his Mary Handley Mystery series, Near Prospect Park, is set during the 19th century and takes on the sinister misdeeds of New York’s elite. Levy is an award-winning television writer and a member of the screenwriting faculty at LMU SFTV. He’s written for hit TV shows such as Family Ties, Saved by the Bell, and Seinfeld. You can catch Levy discussing detective Mary and her newest case this Saturday, January 18, at the Barnes & Noble in Burbank.

How did the character of Mary Handley come to you?

Years ago, my son wrote a term paper about Thomas Edison, and it got me thinking about telling historical stories through the lens of real murder mysteries of the day. When I started looking for real murderers, I came across Mary Handley, a woman from the 1800s who was asked by the Brooklyn police department to sleuth a high-profile murder. There were not women police officers at this time, so it was highly unusual.

As a writer, I like a good story and I like being surprised. As I developed Mary’s character, she took over the book. She was the person that everyone responded to. I wanted to give her a very human life; she often clashes with her mother, who wants her to get married and not work and be like other women of that era. Later on, she has to solve a murder while taking care of her young daughter. In this book, when she gets involved in a case involving a crime against another woman, it brings up many emotions for Mary. In that way, Near Prospect Park has a stronger emotional core and is darker than the previous books in the series.

Kirkus Review called NEAR PROSPECT PARK a “shocking #MeToo story,” in reference to the plot involving Stanford White, a prominent man of the time whose crimes against women closely mirror those making headlines today. While using historical figures like Thomas Edison, John D. Rockefeller, and Teddy Roosevelt in the mysteries is a hallmark of the series, why did you want to tell this story in particular?

When I came across this case, the parallels with today’s #MeToo movement struck me. Readers may not realize it at first, but Stanford White was a real person. He was a very successful architect in the late 19th century and a powerful man. His sex crimes were reported to authorities, but no one ever believed the young women reporting them. To me, people needed to understand that these sorts of crimes have been happening throughout the ages. It’s not a recent problem, and it’s got to stop.

I think readers appreciate the fact that I use historical figures in the series but show them as real people and use them on both sides of the mystery. In previous books, for example, Mary befriends Teddy Roosevelt, who was the police commissioner of New York at the time. He helps her when she’s sleuthing the case and becomes an ally.

How is your approach to writing for TV different than writing for novels?

Television is more collaborative, so sometimes it turns out better than you’d expect, but a lot of times it turns out worse than you’d expect. What I like about TV is that when I write something, it’s shot, and then it’s out there in the world fairly soon. Books take longer. When I’m writing a novel, I don’t have to depend on other people to get my point across. I get to say what the characters feel, what they’re thinking, and what they’re doing. My TV writing experience helped me a lot with the novel, interestingly enough. In most television, especially in sitcoms, the structure is very strict to allow for commercial breaks. So as a writer you become very focused on creating act breaks that offer some surprise or some fun thing to keep people coming back, and that approach is very similar to writing a book’s chapters.

What advice would you give to aspiring writers looking to get their work out there?

First, write a pilot you love. Forget about what other people have done; forget about what you think will sell. Of course, you have to know how to structure a pilot, but when you write something you really love, it shows. Second, remember to keep your perspective. You have to keep your business mind going and know what you want. That’s not to say that I’m not flexible, I’m always willing to take notes. You have to be willing to make changes and to be collaborative, but you also have to feel good about the decisions you’re making during the creative process. Finally, keep in touch with each other. I always encourage my students to stay connected because you never know who’s going to get their first break. You never know who’s going to find out about opportunities first—maybe your friend doesn’t have the script their contact is looking for, but you do, and your friend will connect you with that person. I’d say about 95 percent of the work I’ve gotten has been through networking this way.

You’ve worked on so many iconic series—Seinfeld, The Love Boat, Ahhh Real Monsters—so tell us: Which did you prefer working on, Seinfeld or Ahh Real Monsters? Who would win in a fight: George or Kramer? Are there any classic comedies you’d love to reboot?

Larry David is very talented. I enjoyed working with him very much on Seinfeld, but I’m always proud and surprised when people tell me how much they liked Ahhh Real Monsters. Definitely Kramer would win in a fight versus George. I’d like to see a remake of Buffalo Bill, the 1980s comedy about a newscaster with a ton of ambition. It had the sharpness of today’s comedies but was perhaps a little too edgy for its time.