The 1992 uprising in Los Angeles dramatically changed many lives, including the life of Emelyn dela Peña, LMU’s vice president for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. On the 30th anniversary of those events, dela Peña reflects on what changed for her personally, and what was revealed about the bigger challenges of diversity, equity, and inclusion: “This was a turning point in my decision to become a professional in higher education.”

I’m humbled to offer this reflection as the new vice president for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion at LMU. While new to this campus, my work has been centered in social justice for almost 30 years. In my professional and scholarly practice, I seek to foster understanding, community, and belonging; but more importantly, I commit to living out these values of an inclusive and just community through a broad array of programs, initiatives, and difficult conversations that permanently embed diversity, equity, and inclusion into the fabric of our academic, residential, and work environments. This commitment has been informed by early experiences with marginalization as well as several critical incidents that have shaped my philosophy and practice regarding social justice and diversity.

Critical Incidents

Bobbi Harro defines a critical incident as one that “creates cognitive dissonance” (Bell, Adams & Griffin, 2007). These incidents can be experienced as a one-time event or over the course of multiple moments of dissonance that cause an awakening in our consciousness. While I’ve had a few critical incidents in my lifetime that have led to my calling in this work, one of the most influential in my career trajectory in higher education was the Los Angeles Uprisings in 1992.

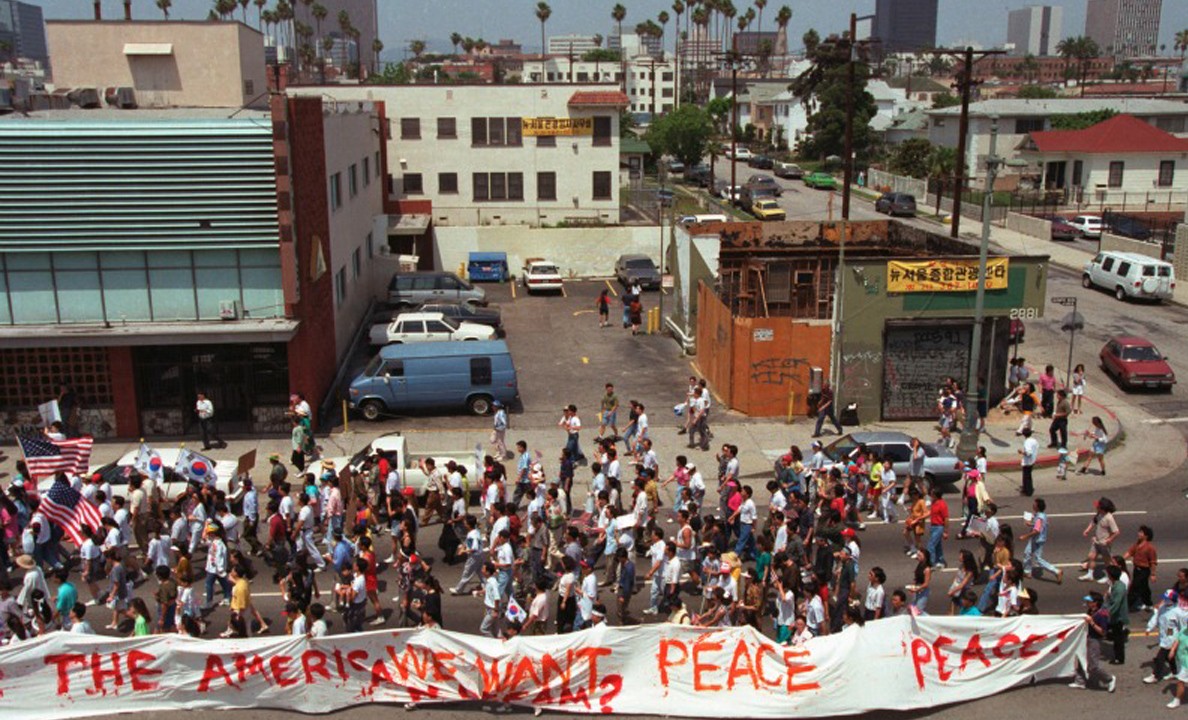

On April 29, 1992 the verdict was announced acquitting four LAPD officers caught on camera beating an unarmed Black man (Rodney King). I was a sophomore in college at UC San Diego, my family about 100 miles away in Los Angeles. While classmates demonstrated by marching through campus and blocking Interstate 5, I made a conscious decision to go to class. Some of my student activist friends criticized my particular act of resistance, but I told myself that day that I was going to graduate and return to a predominantly White institution in a very affluent neighborhood, to make a difference for a student like me — first generation, woman of color from a working-class background who went to school in inner city Los Angeles. This was a turning point in my decision to become a professional in higher education at a time that also saw the emergence of a new field of scholarship about campus climate issues.

I didn’t know then there was a field of study and professional practice in higher education. I had no idea what this commitment to “make a difference for a student like me” would look like. But the images of Rodney King, the trial, and the verdict awakened in me the desire to do something different with my life. Up until that point, I was studying to be an engineer. At the end of my sophomore year was when I left engineering, first for quantitative economics and decision sciences, then four changes in major, and three quarters of calculus, differential equations, and linear algebra later, to a bachelor’s degree in ethnic studies. Since then, this has been my lifelong calling — rising to the challenge of addressing injustice and inequity within the institutions I’ve worked and communities I’ve lived.

The Call to Be JEDI

Thirty years later, while I can say so much has changed in the ways we think about diversity and social justice, particularly on our college campuses, I also realize that I could read a set of recommendations in the archives from 50 years ago, and they would still be relevant today. We have new scholarship, tools, and language about how to achieve equity, yet we continue to have deep seated challenges with race relations, justice, and inclusion. What remains constant is that “diversity is a call to action, a verb, something that one can demonstrate, behave, and enact” (Winkle-Wagner & Locks, 2014). In this way, the practice of diversity is about more than celebrating all the ways we are different, but working towards equitable outcomes, ensuring BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color), minoritized, and marginalized members of our community feel affirmed, and intentionally bringing people together to feel a sense of belonging and community on our college campuses.

Our campus communities are calling on us to do more than give lip service to diversity, equity, and inclusion. Our statements in support of marginalized and minoritized communities must move beyond professions of caring toward commitments to enact structural and institutional change. In short, we are called to “BeJEDI” – Belonging, Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion – and to embed these principles and practices beyond the offices formally charged to do this work.

From Moments to Movements

Being JEDI also means shifting from an “appreciation” of diverse identities to challenging oppressions based on identity. Celebrations of otherness may engender positive feelings temporarily, but run the risk of creating an environment where diversity is performative. Too often across the country, students, staff, and faculty are asked to take part in climate assessments, yet no action is taken from the data. We want to change that dynamic here at LMU. BIPOC folks are often called to respond in “moments” of crisis, yet our communities do not change when the moments are over. Our challenge is to take the energy from these highly visible and emotionally charged moments (like the uprisings in L.A., Ferguson, and Minneapolis) to build movements. In order to do this, our commitments to belonging and inclusion must acknowledge the legacies of white supremacy and injustice on our campuses. We cannot continue to profess “this is not who we are” when crisis incidents happen. Those of us who experience daily injustices know very well this is who we are. Authenticity and compassion require us to be honest that “this is not who we want to be.”

My own growth as a BeJEDI practitioner has been influenced by current social movements and issues, such as Black Lives Matter, multiple pandemics caused by a global health crisis and anti-Black racism, and theft of indigenous land. It has become increasingly clear that building individual capacities for equity work without creating a community of BeJEDI practice means leaving individuals with feelings of being alone in the work, frustration, burn out, and silos. This is particularly true for those of us who “do diversity” on our campuses while occupying multiple minoritized identities. Occupying a liminal space is a key component of the lived experiences of diversity practitioners on college campuses, often navigating the “warring ideologies” (Saldivar-Hull, 2000) of social justice warriors and agents of the institution. This is why it’s so important that this movement be for and with each other.

Conclusion

My entire professional career has been centered on belonging, justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion. This commitment has been influenced by a diversity paradigm of “right the wrongs” (Palmer, 1989). As such, my work has been grounded in a commitment to taking action for change. I have done so in order to create communities where all members can thrive and where students, staff, and faculty can share frustrations, failures, and strategies with courage and honesty.

I’m excited to begin this journey at LMU and to be here as we commemorate the rebellion that set me on this path. My intention in reflecting on this pivotal time in my own history as a change agent is to call us to action in achieving our espoused goals of creating a just and equitable campus with the belief that acts of revolution are acts of love. The ultimate compliment I have received during my career was from an alumna of Harvard College, who was a freshman when I first arrived and who became my colleague after she graduated. When I announced I was leaving Harvard, she commented, “because of you this place is different.”