“I’m delighted you all are here for this weird and wonderful adventure into our collective imagination,” said Stacey Cabaj, assistant professor of acting and pedagogy, at Hannon Library’s Faculty Pub Night this past January. The adventure is the subject of a multimedia research project exploring the use of technological synesthesia called “The Sound of Touch,” which Cabaj is creatively exploring with Christine Breihan, LMU theatre arts lecturer, and Frank Jason Sheppard, theatre arts technical director.

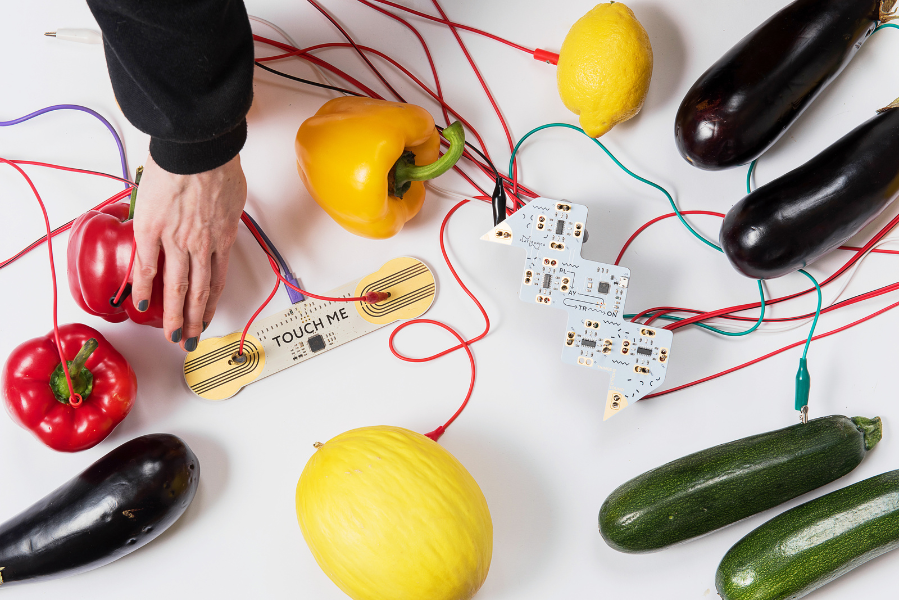

The project was born in 2021, when Cabaj received an American Fellowship from the American Association of University Women to explore the educational and theatrical application of new technologies by Playtronica, a German studio and start-up. Using Playtronica’s innovative musical devices, Cabaj transformed touch between people and objects into sound. This process is known as intentional technological synesthesia, the mixing of senses.

Cabaj was connected to Breihan, at the time a graduate student in the performance pedagogy M.F.A. program, through the RAINS Research Assistant Program. By chance, Breihan experiences synesthesia, a neurological condition present in only about 3 percent to 5 percent of the population. For many years, synesthesia was not studied as some scientists dismissed it as a product of an overactive imagination. But the work being done to explore this occurrence is now redefining how humans perceive the world and our surroundings.

“Our project came out of the pandemic,” said Cabaj. “We noticed how technology mediated presence and how the pandemic changed the way we relate to each other, especially with proximity and touch.”

The multidisciplinary project is on the cutting edge of new creative technologies and allows a form of expression that had been stifled during the pandemic when physical distance was the norm and human connection was often scarce. “There’s a lot of interest in using these tools in therapeutic settings, like for play or sound therapy, and also in special education — to support neurodivergence that can celebrate different ways of perceiving the world,” said Cabaj.

“One of our explorations was how touch is used in storytelling,” said Breihan. “We are artists, and touch is a part of what we use to tell the story of the human experience. If you look at the way somebody touched when they shook hands and first met, to falling in love, to maybe departing from one another, those touches would be able to tell the story of a relationship.”

With technical support from Sheppard and LMU theater students, Cabaj and Breihan conducted a three-phase workshop at LMU in November 2021. The first phase was building a movement story from beginning to end about the evolution of a relationship through touch. The second phase explored the lived experience of the pandemic and gave participants the opportunity to share their own pandemic experiences by pre-recording a narrative that was then played when participants touched a conductive object.

“It was very emotional, evocative, and affirming to hear the similarities of their senses, of isolation, longing, loss, and resiliency,” said Cabaj.

In the third phase of the workshop, participants were invited to share what they felt were signature objects or sounds of the pandemic. Those objects included hand sanitizer bottles, protest signs, remote controls, Zoom screens — all things that took on new meaning after the pandemic. The immersive exhibit invited participants to walk through singularly or in a human chain, so that while even one person might be touching an object, the group was experiencing the moment together. The sound of the Netflix logo screen, the clanging of pots and pans, the voice of former President Donald Trump, people coughing, and crying all played at different times as participants walked through the exhibit together.

Because of the relatively inexpensive and user-friendly nature of the tools and technology, Cabaj hopes to expand the number of Playtronica devices that LMU owns to allow for student and faculty experimentation on campus.

“I’d love to hear what the Foley fountain sounds like,” said Cabaj. “I would love someone to explore the bluff with a friend and see what music is to be made here, which will give us a greater appreciation for the paradise in which we live and work.”