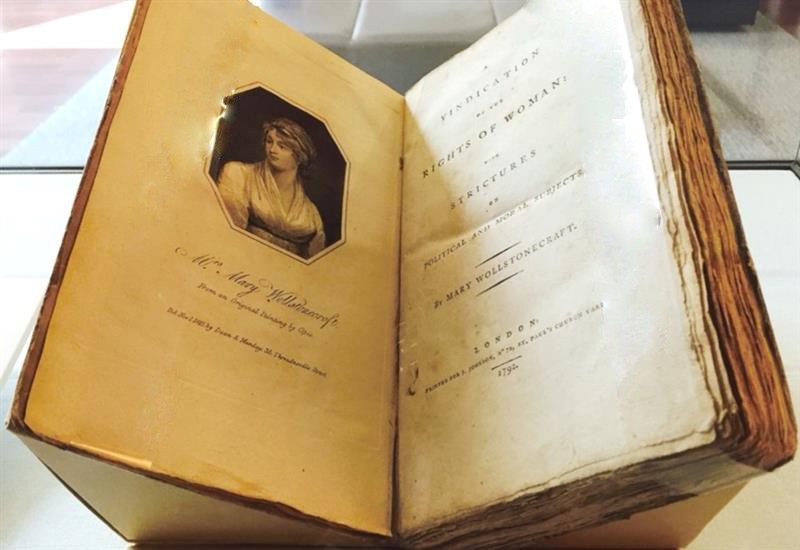

Perhaps there is no better way to kick off the celebration of Women’s History month then to spotlight the unique artifact donated to the William H. Hannon Library in the 1960s by pioneering woman donor T. Marie Chilton: An original edition of Mary Wollstonecraft’s seminal feminist work “Vindication of the Rights of Woman: With Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects,” printed in 1792.

Wollstonecraft (1759-97) was born near London, England, the daughter of a farmer who was often drunk, abusive and had largely squandered the family’s vast inheritance. During Wollstonecraft’s time, women did not attend university or work outside the home unless they were part of the working classes who took part in farm or menial labor (Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2022). Yet by the age of 19, Wollstonecraft had defied her parents and society by taking paid jobs as a companion to the elderly; a schoolteacher and founder of a boarding school; a governess to a prominent Irish family; a contributor to political journals and later a prominent author.

Though Wollstonecraft came of age during the Enlightenment, it was also a time when women were treated as the “inferior sex,” becoming property of their husbands once married and unable to vote, hold office, own property, or pursue a comparable education to men. In Wollstonecraft’s time, women’s education consisted largely of learning to cultivate “female appropriate” skills such as sewing, gardening, piano, artistic or charitable pursuits expected to help them become suitable wives and mothers.

Nowhere in European society at the time were financial, social, educational, or legal rights offered to women in a manner that even began to approach those afforded to men. Although Enlightenment thought had taken hold, this was largely a philosophical movement of influential men, including Jean-Jacques Rousseau and James Burgh, both of whom wrote directly of women’s necessary dependence upon men (Rousseau, 1762) and the need to “protect their chastity” (Burgh, 1774).

As a rare independent woman of her time who generated her own income and lived in her own residence, Wollstonecraft reacted strongly to these prevailing views and became a passionate advocate of women’s’ educational and social equality. Already a prominent political voice with the 1790 publication of her “Vindication of the Rights of Men” – a direct challenge to Edmund Burke’s published anti-revolutionary reflections on the French Revolution – Wollstonecraft’s “Vindication of the Rights of Woman” was written as a direct follow-up in which she makes a commanding case for educating and emancipating women. Wollstonecraft argues that women are made to appear inferior through a lack of equal education and resources afforded them by society (Minnesota Peacebuilding Leadership Institute, 2018). “I do not wish [women] to have power over men; but over themselves,” states Wollstonecraft in this seminal work.

Today, Wollstonecraft’s “Vindication on the Rights of Woman” is largely considered to be the origin of modern feminism. Although other early feminists made similar pleas to improve education for women, Wollstonecraft’s “Vindication” was unique in that it argued that the educational system for women of her time deliberately trained women to be frivolous and ineffectual in society; and that the betterment of women’s status could best be enacted through a sweeping reform of national educational systems. Such change, she noted, would benefit not only women, but all of society.

Echoes of today’s themes in the continued fight for racial justice and equality can be seen throughout the “Vindication” treatise, as this well-known quotation illustrates: “Contending for the rights of women, my main argument is built on this simple principle, that if she be not prepared by education to become the companion of man, she will stop the progress of knowledge, for truth must be common to all, or it will be inefficacious with respect to its influence.”

Though Wollstonecraft died days after giving birth to her second daughter (the writer Mary Shelley, best known for “Frankenstein”) her legacy continues to be celebrated. Claiming that men and women should be treated equally in a society that is based on reason, Wollstonecraft’s “Vindication of the Rights of Woman” places her as arguably one of the “first feminists” of Western thought and literature. “Strengthen the female mind by enlarging it, and there will be an end to blind obedience,” she stated. “The beginning is always today.”

The Wollstonecraft original edition of “Vindication” is housed in the William H. Hannon Library and is a standout artifact in a collection that is, itself, a standout collection provided generously by another pioneering woman, T. Marie Chilton. In 1972, Loyola Marymount University received the largest single bequest in the school’s history at the time, a $3 million gift by Chilton, a philanthropist and antiquarian book collector. Chilton’s interest in the university coincided with the opening of the Von der Ahe Library in 1959, and in her lifetime, Chilton loaned the library her collection of 400 rare books.

According to Cynthia Becht, head of Archives and Special Collections at the William H. Hannon Library, Chilton gifted her rare book collection in the 1960s, and her donation was a momentous gift that helped to establish Special Collections at LMU. The Chilton Collection gift includes not only this rare original Wollstonecraft work, but other incredible standouts such; Dante’s “Divine Comedy,” from 1481, illustrated by Botticelli; four 17th century folio editions of Shakespeare, including the much-prized First Folio; and first editions of works by Jane Austen, Charles Dickens, C. Thomas Hardy, John Keats, Rudyard Kipling, Lord Alfred Tennyson, William Thackeray, Mark Twain, H.G. Wells, Edith Wharton, and Oscar Wilde, among others, many of which are signed or presentation copies and held at the library. Additionally, the Chilton Collection contains two volumes from the library of George Washington that bear his signature.

“I like to compare [T. Marie Chilton] to the ‘Downton Abbey’ characters,” Becht said. “She was an American heiress of that period, and quite elderly when she formed a relationship with Loyola University [and generously donated her rare book collection]. I’ve always been grateful that our most-generous donor to special collections – and at the time of her donation, to the university – was also a woman.” Indeed, offering such a generous gift to LMU as a woman, a book collector, and a champion of literature, Chilton seems to have embodied the principles of the importance of education and industriousness that Mary Wollstonecraft established in her seminal work.

This month, as we seek to honor all those women who came before us who have forged the way to equal rights, education, and independence, let us not forget these notable figures: Wollstonecraft and, 200 years later, one of her collectors and generous supporters, T. Marie Chilton.

By Sheri Castro-Atwater

Professor, LMU Counseling Programs

Brittanica (2022). Mary Wollstonecraft, English Author.

Lewis, Jone Johnson. (2021, September 8). Mary Wollstonecraft Quotes.

Selected Research Papers and correspondence, T. Marie Chilton, (including E T. Marie (Dunbar) Chilton Fact Sheet, compiled by Errol Stevens). Shared with author 2/2022 via email courtesy of Cynthia Becht, Head, Archives and Special Collections, LMU’s William H. Hannon Library.

T. Marie Chilton Chair in Catholic Theology.

Taylor, B. (2016) The Social and Political Philosophy of Mary Wollstonecraft, pg. 216. London: Oxford University Press.

“Wollstonecraft, Mary.” Encyclopedia of World Biography. (Retrieved Feb. 28, 2022)

DEI Buzz

- Join Us: Today for our Systemic Analysis Report Out Session from 4-5 p.m. PST. Units can share their progress and receive feedback from the community. Register here.

-

- March 8, 4-5 p.m., SOE, Marketing and Communications

- March 29, 4-5 p.m., Mission and Ministry, Student Affairs

- Check Out: DEI’s spring 2022 calendar.

- Celebrate: Women’s History Month with LMU: https://lmu.edu/whm