In fall 2022, my long-term colleague, Professor of English Holli Levitsky and Director of Jewish Studies at LMU approached me to share hers and Rabbi Mark Diamond’s initiative to create two Greek-Jewish fellowships to sponsor student work in June-July 2023 on-site at the Romaniote Etz Hayyim synagogue in Hania, Crete.

Rabbi Mark introduced us to the Director of the Etz Hayyim synagogue, German historian Anja Zuckmantel, who, on behalf of the not-for-profit corporation Etz Hayyim, has been operating a decade-long program on Crete to educate visitors about Jewish history and annually memorialize those citizens who perished during World War II.

Prof. Levitsky has supported my work on Connecting the Liberal Arts, Classics and Film, co-sponsoring the 2016 LMU screening of the documentary Kisses to the Children (dir. Vassilis Loules), which included the stories of five Jewish children who survived the Holocaust hidden by Greek families. One of the most heart-wrenching WWII stories was the sinking of Tanais that carried all 268 Jews of Crete, along with 48 Christian Greeks and 114 anti-Mussolini Italian prisoners of war, shortly after leaving the port of Heraklion on June 8, 1944. One of the survivors interviewed in the film with whom I kept in contact, poet Iossif Ventura, who escaped the fate of the Cretan Jews by escaping the island to Athens with his family and by passing as the son of his Greek nursemaid, is today a member of the Etz Hayyim Board of Trustees.

From the outset, therefore, I embraced the LMU fellowship program for Etz Hayyim with great enthusiasm and even shared with all collaborators a cherished memory from our family annals that seemed aptly pertinent:

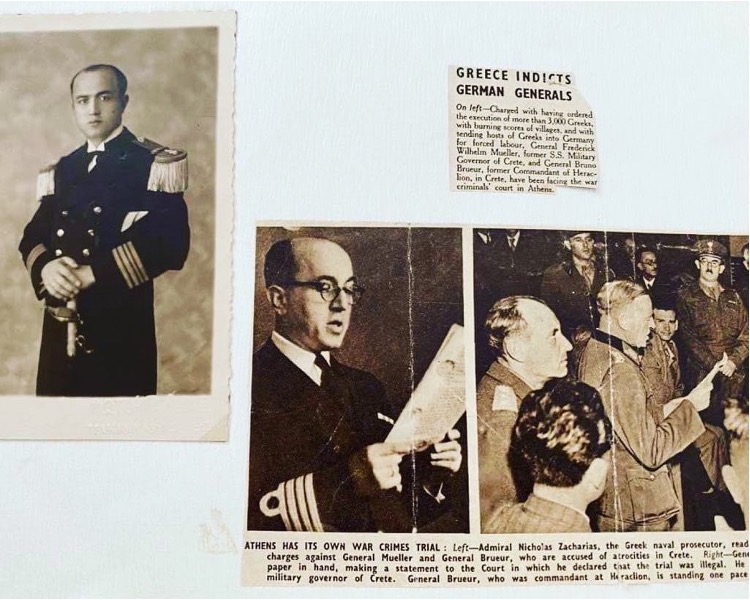

My paternal grandfather, Nikolaos M. Zacharias, first of nine children, had traveled from the Aegean island of Ios to Athens to study law. After rising to the rank of Admiral in the legal branch of the Greek navy, he served as naval prosecutor in the Nazi war criminals’ court in 1947 in Athens. He successfully indicted with “having ordered the execution of more than 3,000 Greeks, with burning scores of villages, and with sending hosts of Greeks into Germany for forced labor,” two Generals: (i) Friedrich Wilhelm Mueller, former Wehrmacht Military Governor of Crete, a member of the regular German army (not the SS), and (ii) Bruno Bräuer, former Commander of “fortress Crete,” who had also issued the order for the arrest and deportation of the Cretan Jewish community. The two Generals had unsuccessfully attempted to dismiss all accusations by declaring the trial “illegal,” as was reported in national newspapers at the time.

In preparation for the indictment, Nikolaos M. Zacharias and his team had conducted a thorough investigation compiling evidence for the trial against the defendants. My grandfather, who maintained during his entire life his vehement opposition to the death penalty, found himself in a moral dilemma. He sought recourse in his faith and went to confession with the question: “Who am I, and how am I different to these two Generals, if with my indictment and ensuing conviction I seal their execution? Is our only difference in numbers of people killed, since I will be responsible for the death of the two Generals who have signed off the execution of over 3,000 people?” His priest reportedly inquired if my grandfather had secured a conviction based on reliable evidence, and when my grandfather assured the validity and irrefutable weight of evidence, the priest admonished my grandfather to fulfill the responsibilities of his elected position. This incident serves as a further illustration of my grandfather’s integrity and precious legacy, and is the reason why I dedicated to him my first undergraduate essay against the death penalty.

Grateful for the opportunity to honor my grandfather’s legacy, I was immediately supportive of the newly founded LMU Greek-Jewish fellowships in Hania. The more I learned about the ancient Greek synagogue resurrected by Nikos Stavroulakis (1932-2017), the more I became invested in propounding the merits of the Etz Hayyim Center. Dr. Stavroulakis was born and raised in Wisconsin to immigrant parents, studied in the USA, UK, and Israel, and moved to Athens in 1958, where he became the founding director of the Jewish Museum of Greece. In the 1990s, he galvanized international interest and was successful in rebuilding and rededicating Etz Hayyim, remaining the synagogue’s spiritual director until his death.

One of the two inaugural recipients of the Greek-Jewish summer fellowships was Clara Goolsby ’24, a biochemistry and classics and archaeology double major , who wishes to pursue a career in museum conservation. As a sophomore in spring 2022, Clara had excelled in my course on “Representations of Greece: Ancient and Modern” and in the embedded internship with the Los Angeles Greek Film Festival (LAGFF). Clara helped me build the course website documenting the decade-long LMU-LAGFF community partnership. Furthermore, in spring 2023, Clara received a Citi Bank funded internship at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) Conservation Center in the Conservation Research department. Given her qualifications and interests, Clara was tasked to catalogue the Nikos Stavroulakis Collection of personal and academic manuscripts and correspondence, photographs, artefacts, liturgical and personal items. She completed the digitization of the archive in July 2023, and even left guiding notes for her successor.

My airfare was subsidized by the LMU Jewish Studies program, so I was able to accompany Clara to Hania for a three-day visit during the first weekend in July. During my stay, Anja had arranged for us to attend a bat mitzvah in Etz Hayyim and participate in all weekend festivities. The generosity of the Liebgott family for including myself and Clara in their group of international visitors from the Czech Republic, the USA, Israel and South Africa, was a delightful surprise, as was the wonderful interfaith community that Anja introduced us to at the Etz Hayyim Center. As it transpired, this interfaith component was an intentional principle founded by the visionary Director, Dr. Nikos Stavroulakis.

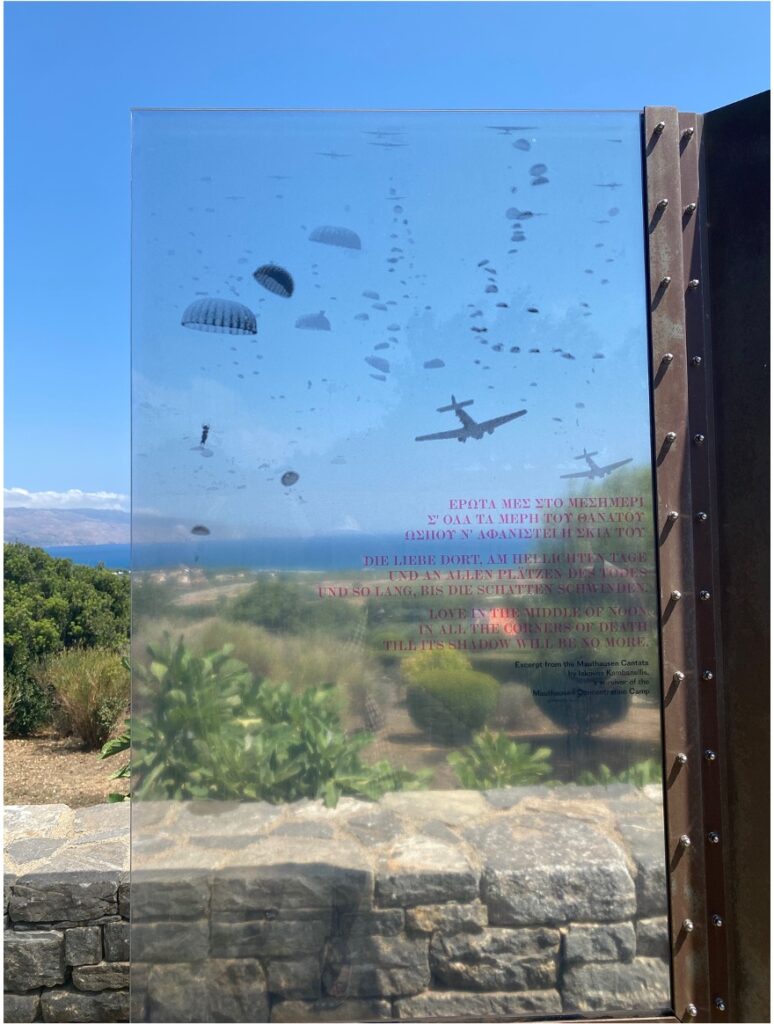

On July 3, given my family history, Anja arranged for the LMU group to visit the “Maleme Historical Memorial Site for the Battle of Crete 1941,” near Hania. On that airfield in May 1941, German airborne paratroopers were dropped as part of the Nazi operation to capture the island. Before conquering the field, the Germans suffered a heavy toll of casualties inflicted by the Cretan local resistance and their English, Australian, and New Zealand allied forces.

The German military cemetery in Maleme (1939-1945) was founded in 1974 by the former German commander Gericke for the fallen soldiers in the four main battle grounds of Crete, namely Maleme, Chania, Rethymnon, and Heraklion. The care of the cemetery is done by the “The German Graves Commission,” a private association based in Kassel and founded in 1919 after the First World War, ordered by the German government.

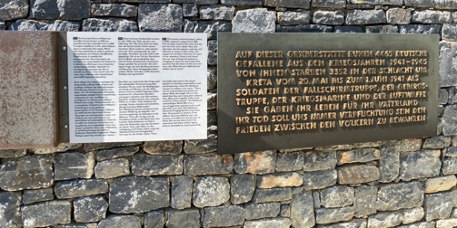

In Maleme, 4,465 German soldiers are buried, many of whom lost their lives during the first airborne invasion “from May 20-June 1, 1941,” as the bronze memorial plaque at the entrance of the cemetery attests:

German military cemetery in Maleme

Memorial plaque

“This bronze memorial plaque, added in 2002, replaced a plaque from 1988. The wording remained the same, but the last two lines were added. Now, decades later, the text appears untimely and offensive to many. In spite of this, the plaque has not been removed. It is part of the cemetery’s history and shows how our view of historical contexts is changing. It raises the most important question that all visitors to this war cemetery ask: What did over 4,000 German soldiers die for here? Inevitably, that leads to the deeper question of individual responsibility in war and dictatorship, which the Volksbund answers as follows in its vision: ‘There can be no generalized attributions of blame: Many were culpable. Others had no choice. A few resisted.’ The Volksbund acknowledges World War II as a war of aggression and destruction, and describes it as such. The Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge looks after these graves in memory of the millions who were killed by wars and tyranny, in an effort to ease the pain of those who survive them, and in the awareness that these victims’ legacy exhorts all peoples to coexist peacefully.”

The phrase that remained unchanged in the 2002 plaque is highlighted below in bold and brings with it echoes of the Third Reich:

“On this gravesite, there are 4,465 Germans who fell in the war years 1941-1945. 3352 of them died in the Battle of Crete from May 20 to June 1, 1941, as soldiers of the paratroopers, the mountain infantry troops, the navy, and the air force. They gave their lives for their fatherland [“sie gaben ihr Leben für ihr Vaterland”]. Their deaths shall always be our obligation to keep peace among the people.”

In the short exhibition space near the entrance, the fallen German soldiers are introduced as young men whose lives were cut short, and there is an effort to remember them as individuals with dreams and aspirations and not just as casualties of war. I was struck by the exhibition section on war crimes and registered the candid acknowledgment:

“Research is currently ongoing to ascertain the perpetrators of Nazi war crimes. The Volksbund acknowledges that war criminals are buried alongside ordinary soldiers in many war cemeteries. For this reason, there is no honorable commemoration of the dead. However, it is imperative that we remember the events – to prevent future war and tyranny.”

As I walked up the incline to the cemetery, I was taken aback by the immaculately manicured gardens and the prime location overlooking the bay.

German cemetery in Maleme

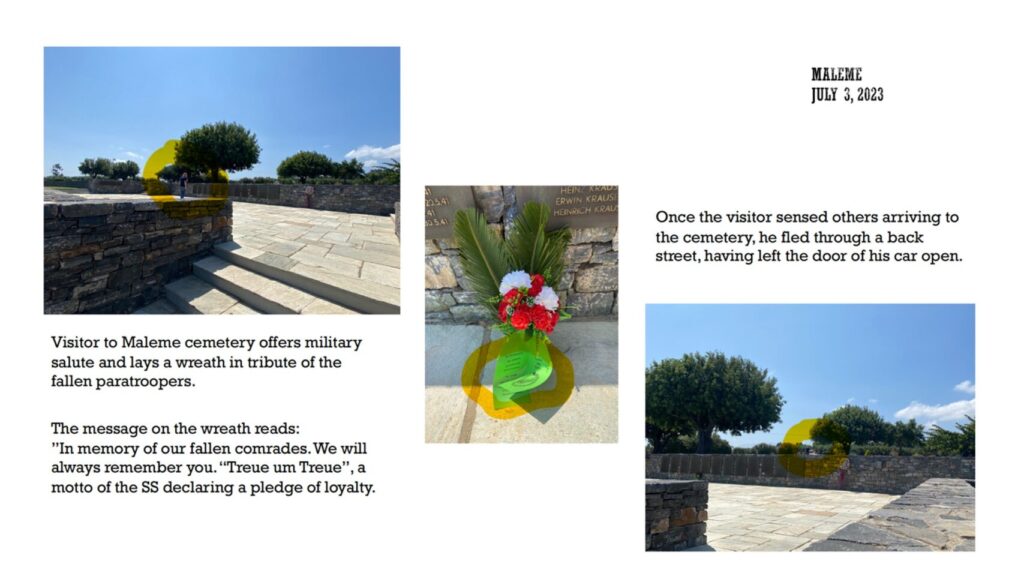

While taking a few photos, I realized that a visitor was offering a military salute to the fallen (see picture down left). Upon my arrival, he fled the scene walking quickly to a back street where his car was left with the driver’s door open (see picture down right). I then realized that the visitor had just laid a wreath with the Nazi emblem of the paratroopers and the message: “In memory of our fallen comrades. We will always remember you.” Incidentally, the German phrase “Treue um Treue,” a motto of the SS declaring a pledge of loyalty to the Nazi party, has been banned in the German army since 2014, when its strong connection to the Wermacht was established. The incident I witnessed was the second occurrence in Maleme. The first incident was recorded on May 28, 2023 in the same cemetery, during a well-attended German state-sanctioned ceremony in the presence of the Defense Attaché of the Embassy in Athens, who delivered a speech on behalf of the German Ambassador, and included representation from the Federal Association of Paratroopers (Bund Deutscher Fallschirmjäger e.V.). At that time, left-wing MP Andrej Hunko had inquired in the German Parliament about the involvement of the German Ministry of Defense and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the German Embassy.

Dumbfounded and shaken by this glaring neo-Nazi behavior, we approached the Greek gardeners who have been keeping up the cemetery grounds since 1974, who confirmed that in recent weeks, many such visitors sneak through the back entrance to the cemetery and perform similar actions.

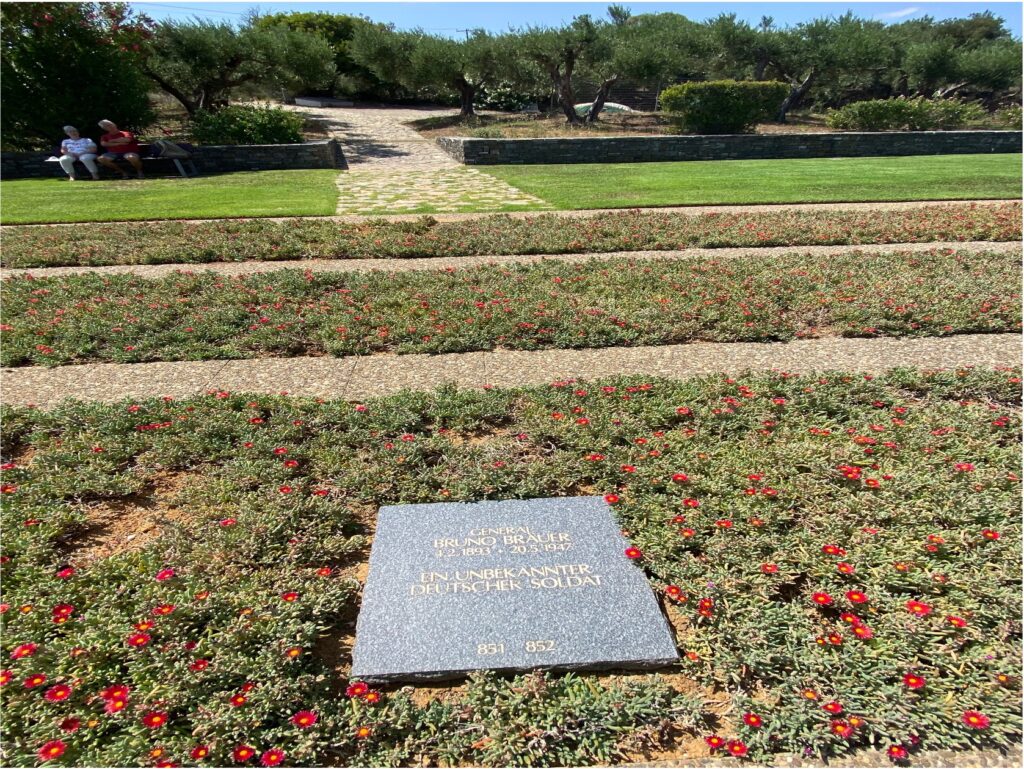

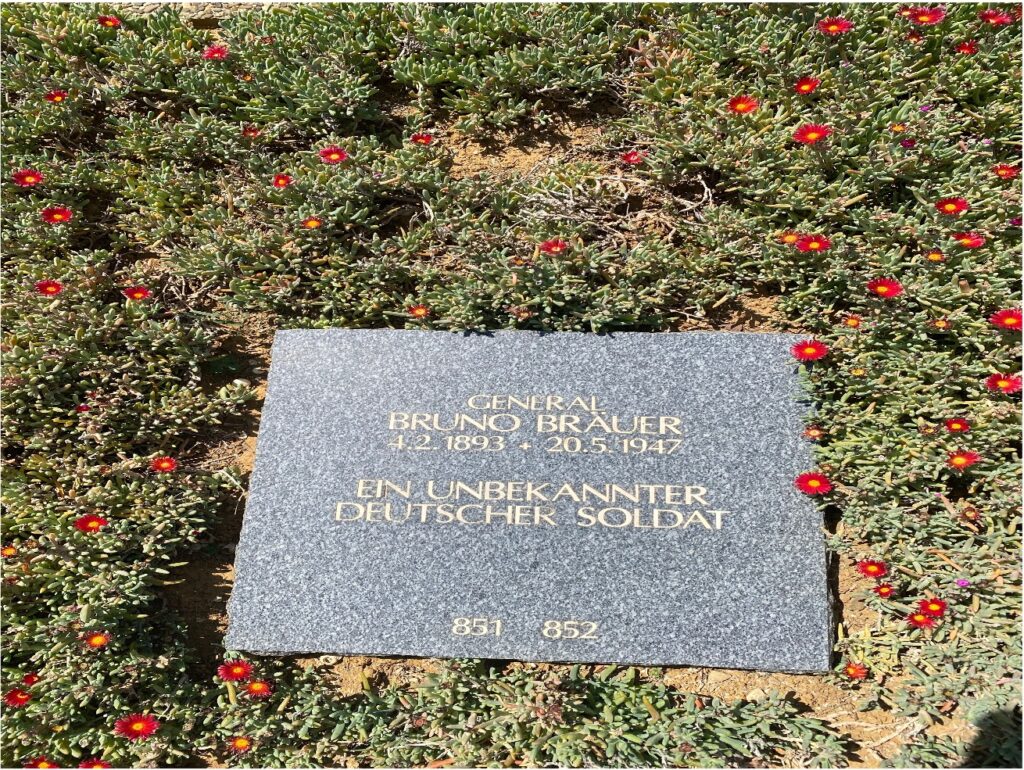

The gardeners also pointed us to the tomb of the court-martialed General Bruno Brauer, the very war criminal my grandfather indicted and convicted in 1947. His tomb is strategically located for easy access through the back path to the cemetery (see below). Now, the carefully articulated acknowledgment in the Maleme exhibition space that “war criminals are buried alongside ordinary soldiers” and “For this reason, there is no honorable commemoration of the dead” is alarming, given the neo-Nazi stealthy tributes to the German occupiers of Crete in 2023, the year when neo-Nazi parties have been reelected in the Greek Parliament holding over ten percent of the seats.

Tomb of General Bruno Brauer

The urgency of redressing the rise of white supremacy and extreme right ideologies in Greece and Europe is pressing.

Throughout 2024, the not-for-profit corporation Etz Hayyim as the official organizer, in collaboration with many Greek organizations, is hosting a series of summer events commemorating the 80th anniversary of the Greek resistance fighters, the Cretan Jewish community and the allied forces who perished defending their families and homes against the Nazi occupation. LMU is proud to renew the student fellowship program and participate meaningfully in the 2024 events.

By Katerina Zacharia, Ph.D., Professor of Classics and Chair of Classics & Archaeology at Loyola Marymount University