2023 marks the 100th anniversary of the introduction of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) to the U.S. Congress, a monumental amendment that set out to achieve “equality of rights under the law” for people of all sexes in the U.S. Constitution. In honor of this notable centennial, we provide a retrospective look back at how the ERA was formed, how it progressed, and where we are now, including a look at the women and advocates behind this ongoing fight for equality. For despite undergoing a century’s worth of discussion and debate in the public discourse as well as at all levels of government, the ERA has still not been enacted as a federal amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

The ERA’s history begins with the author of the ERA and prominent member of the women’s suffrage movement, Alice Paul. In 1912, Paul and fellow American suffrage advocate Lucy Burns were appointed to the National American Woman Suffrage Association’s (NAWSA) Congressional Committee, and both had been trained in the tactics of Britain’s suffragette movement. Over the next few years, they broke away from NAWSA as they advocated to concentrate on a federal amendment vs. state ratification, leading to their co-founding of the National Woman’s Party (NWP). Throughout the 1910s, the NWP worked tirelessly to organize street meetings where they distributed pamphlets, petitioned, and lobbied legislators, and organized parades, pageants, and speaking tours, including marches and protests in Washington, D.C. to bring attention to the suffrage movement and to lobby the U.S. Congress to act on this issue.

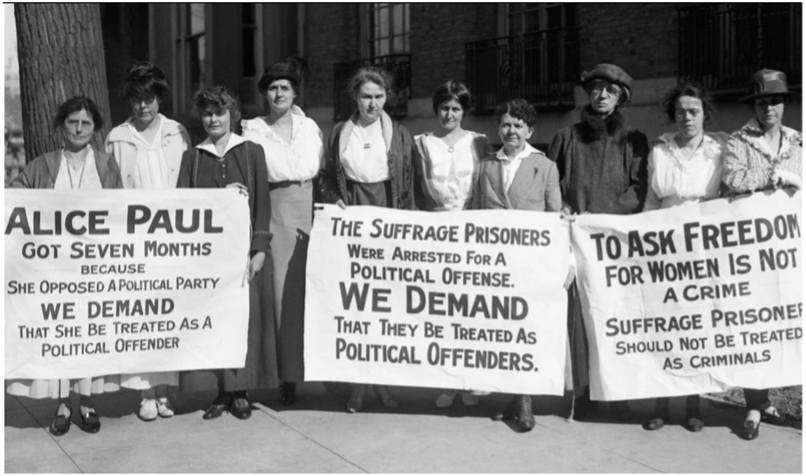

From January 1917 to 1919, Paul, along with thousands of women known as the “Silent Sentinels,” picketed peacefully outside of the White House. Although their protests were non-violent, the women were increasingly attacked both verbally and physically and Paul was arrested, spending seven months in prison under solitary confinement for her involvement. Depictions of women being physically abused, brutalized and force fed while behind bars for their beliefs in equal rights were notably captured in a piece from prominent suffragist Eunice Dana Brannan in the January 19, 1917, New York Times, and caused public consternation, helping the tide gradually turn to increasing public and political support for women’s voting rights. Thanks to the efforts of Paul and her fellow American suffragists, the 19th Susan B. Anthony Amendment was ratified into the constitution in June 1920, giving all women the right to vote.

For Paul, however, the fight was far from over for obtaining women’s rights as citizens. Notably, “women” in the 19th amendment was not inclusive of all women. Many Black women were unable to vote in the U.S. until more than 40 years later when the 1965 Voting Rights Act was passed, due to state laws, violence, and other prohibitive and discriminatory tactics which made voting deliberately exclusionary for Black women despite their U.S. citizenship. Moreover, the 19th amendment only explicitly stated that women were provided with the right to vote and did not outline any other rights women had as citizens or provide them explicitly with the same rights as men, such as their ability to serve on juries, hold public office, own property, work in fields historically closed to them, or even control their own finances.

To address these rights, Paul and others began working on the ERA in 1921. Numerous conversations and debate were held among various groups of women’s rights activists on the proposed text but in the end, Paul’s version was amazingly simple:

“Men and women shall have equal rights throughout the United States and every place subject to its jurisdiction. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.” (Source: https://www.loc.gov/exhibitions/women-fight-for-the-vote/about-this-exhibition/hear-us-roar-victory-1918-and-beyond/ratification-and-beyond/from-nineteenth-amendment-to-era/)

Although Paul found support for her amendment in Senator Charles Curtis (R-KS) and Representative Daniel Read Anthony Jr. (R-KS), who introduced it in their respective houses in December 1923, the opinion of the public and members of Congress were split and it lacked enough support to pass. (Notably, at the time, there was only one woman serving in all of Congress: California Rep. Mae Ella Nolan). What were proponents’ and opposers’ essential arguments for and against the ERA? In her 2021 book examining the orgins of the ERA, “Gendered Citenzship: The Original Conflict over the Equal Rights Amendment, 1920–1963,” historian Rebecca DeWolf notes that arguments presented in Congress and in the press divided into two major camps: emancipationists and protectionists. Emancipationists supported the passage of the ERA, arguing that both men and women could – and should – engage as citizens on the same terms with the same rights. Protectionists, who opposed the ERA, argued for a “gendered citizenship” that legally codified that men and women were inherently different, and because of these differences, should be treated differently as citizens due to their sex.

Although Congress held a number of hearings over the ERA over the subsequent 20 years after its introduction, the ERA never progressed to a vote. It was only during the Depression and World War II – as women took on a number of historically masculine jobs and traditional gender roles were regularly challenged – that public and congressional support for the amendment began to steadily increase. In 1940, the ERA became part of both Republican and Democrat party platforms, and in 1946, nearly 25 years after its introduction, the ERA faced a congressional vote for the first time. Receiving broad support in the Senate, it nonetheless failed to reach the two-thirds majority needed to pass a congressional amendment.

From 1946 until the 1960s, while the ERA was regularly re-introduced to Congress and was the focus of scattered hearings, it lost broad public support as the roles and rights of women were again re-examined, and public imagination glorified the roles of women as mothers and wives. By the early 1960s, both political parties removed the ERA from their platforms.

Paul’s early 20th century concerns regarding the restrictions on the rights of women proved to be prescient and valid, however, for without the passage of the ERA women’s rights in many fields were restricted for decades to come. It was not until 1957 that the Civil Rights Act of that year gave women the right to sit on federal juries, and all 50 states did not pass legislation that allowed women on juries until 1973. It was only in 1974 that the Equal Credit Opportunity Act allowed every American woman the right to open her own credit or bank account, and while the Equal Pay Act was enacted in 1963 to address gender discrimination in the workplace, pay inequities continue to persist, with women still making on average in 2022, 82% of what men make (Pew Research Center, 2023).

By the end of the 1960’s, with the rise of the women’s liberation movement and second wave feminism, public and congressional opinion had again shifted the other direction, and support for the ERA grew exponentially. A growing movement pushed for equal rights for women in economic, domestic, and political spheres. The National Organization of Women (NOW) advocated strongly for the passage of the ERA, and hearings on the ERA were held in Congress beginning in 1970. By 1972, support for the ERA was seen across party lines and had broad public support. It was put back into the party platforms of both the Republicans and Democrats, and a new version of the ERA was put up for a vote in Congress. It now read:

Section 1: Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States of by any state on the account of sex.

Section 2: The Congress shall have the power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.

Section 3: This amendment shall take effect two years after the date of the ratification”.(Source: equalrightsamendment.org/faqs)

The amendment passed both the Senate and the House with overwhelming bi-partisan support and was sent to the states for ratification. Ratification seemed certain. Twenty-two states ratified it in the first year, and then eight more in 1973. After this, however, thanks in large part to a “Stop-ERA” campaign launched by Phyllis Schlafly, an attorney who was a prominent conservative activist, author, and anti-feminist spokesperson for the national conservative movement, ratification slowed down and then stopped entirely. Only three states ratified the ERA in 1974, and only one state in 1975 and 1977, respectively.

The late ratification had profound effects, because unequal to any other constitutional amendment, the proposing clause for the ERA gave a seven-year deadline for ratification by the states. As the deadline in 1979 approached, the amendment was still three states short of the 38 needed to ratify the amendment and add it to the constitution. Congress passed a law that extended the deadline to June 1982, but even with the additional three years, no other states ratified the amendment, and five states even argued to withdraw their ratification. The Republican party withdrew the ERA from its platform in 1980.

While the ERA now seemed doomed, numerous advocates for women’s rights, politicians, and legal experts refused to let it die. The ERA was regularly re-introduced to Congress over the next four decades, and strategies were made for its ratification. In the late 2010s additional movement on the amendment was made, with a re-envigored interested in the ERA after the election of Donald Trump in 2016 and the erosion of Title IX protections, birth control and abortion rights that restricted the rights of women.

Campaigns to bring the ERA back into the public consciousness were launched in a number of states and were successful. In 2017, Nevada ratified the ERA, the first state to do so in forty years. Illinois followed in 2018, and in 2020, Virginia became the 38th state to do so, allowing the U.S. to finally reach the number of states needed to ratify a constitutional amendment.

Yet, although 38 states have ratified the ERA, it has still not been added to the U.S Constitution. Lawmakers and courts continue to argue over whether these additional ratifications are valid, given that they came after the 1982 deadline, and legal challenges have been launched. While the ERA is still introduced in Congress each session, and lawmakers have introduced legislation to extend the deadline and recognize the recent ratifications, today, positions on the ERA are divided largely on party lines (Democratic lawmakers tend to support it with Republicans opposing).

Where do we stand with the ERA being ratified in the Constitution in the 2023 era? The ERA has met all the constitutional requirements for an amendment, with a necessary 38-state ratification. In January 2022, Illinois and Nevada, two of the three most recent ERA-ratification states, filed yet another federal appeal in their ongoing lawsuit seeking to ensure the federal government acknowledges the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) as the 28th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution after the U.S. Archivist refused to enter it into the Constitution as an official amendment (Virginia, the most recent to ratify the ERA, dropped out of the lawsuit in 2022). The suit continues to hinge on the legal debate on whether the ERA can become an official U.S. Constitutional amendment given that the 38-state ERA ratifications necessary to amend the Constitution were not done “by the deadline” originally written into the ERA. Congress has introduced legislation to remove the deadline language and we wait, in 2023, to see whether the legislation will garner enough support in both the House and Senate.

Publicly, the passage of the ERA as an amendment continues to be an important goal for many Americans, with organizations such as the Equal Rights Amendment organization offering resources and toolkits for those who want to help their states ratify the ERA amendment or push for federal ratification. Perhaps most notably, public opinion surveys continue to show that the public overwhelmingly support the passage of the ERA – or are even unaware that it has not already passed (Pew Research Center, 2020).

References

American University Profile Page(2023). Rebecca DeWolf Adjunct Professorial Lecturer, Department of Government. https://www.american.edu/spa/faculty/rdewolf.cfm

Bowman, K. (2021). Women Making History: Polls on the Equal Rights Amendment. https://www.aei.org/politics-and-public-opinion/women-making-history-polls-on-the-equal-right-amendment/

Congressional Research Service (2022). The Equal Rights Amendment: Recent Developments. Retrieved from:https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/LSB/LSB10731

Equal Rights Amendment. https://www.equalrightsamendment.org/

Hartley-Kong (2020). Radical Protests Propelled the Suffrage Movement. Here’s How a New Museum Captures That History.https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/radical-protests-propelled-suffrage-movement-heres-how-new-museum-captures-history-180976114/

Illinois Attorney General Press Release (2022). Attorney General Raoul Files Opening Brief with Appellate Court in Lawsuit to Ensure Equal Rights Amendment is Recognized as 28th Amendment. https://illinoisattorneygeneral.gov/pressroom/2022_01/202203.html

League of Women Voters (2023). 100 Years of the Equal Rights Amendment. https://www.lwv.org/blog/100-years-equal-rights-amendment

Library of Congress: Women of Protest: Photographs from the Records of the National Woman’s Party. American Memory. https://www.loc.gov/static/collections/women-of-protest/images/history.pdf

Minkin, R. (2022). Most Americans support gender equality, even if they don’t identify as feminists. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/07/14/most-americans-support-gender-equality-even-if-they-dont-identify-as-feminists/

Politico (2022). Why hasn’t the Equal Rights Amendment been ratified? Retrieved from: https://youtu.be/qAswlpQVToM

University of Nebraska Press Page: Gendered Citizenship The Original Conflict over the Equal Rights Amendment, 1920–1963. https://www.nebraskapress.unl.edu/nebraska/9781496215567/