By Sheri Atwater, professor of counseling and school psychology,

and Becca Okida, LMU Student Affairs Resident Director

It may come as no surprise that, unlike in past national economic crises (e.g. the Great Depression and the 2008 recession) which affected men’s employment more than women’s, the COVID-19 pandemic is disproportionately impacting women and female-identified caregivers in the workforce, particularly women and female-identified caregivers of color (Kindalen, 2020; Landau, 2020).

According to the Center for American Progress’ Current Population Survey (2018) data, 67.5 percent of Black mothers and 41.4 percent of Latinx mothers were the primary or sole income providers for their families, compared with 37 percent of white mothers.2 While both mothers and fathers are stepping up, studies show that female working parents continue to bear a disproportionate share of the burden, spending roughly 15 hours more per week on domestic labor than men since the pandemic began (Krentz, M., Kos, E., Green, A. & Garcia-Alonso, J., 2020). The Institute for Women’s Policy Research, a women-focused think tank, has coined the term “shecession” (Kindalen, 2020) to describe the economic uncertainty, domestic “pull” from work and depressed job numbers that these women now face, many of whom are shouldering the burden of childcare and home responsibilities during pandemic times (Krentz, et al., 2020).

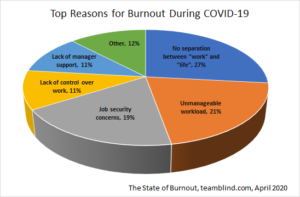

Those who do manage to “do it all” during this stressful time do so at high cost: According to studies from the Maven Clinic (2020), over 2.4 million working mothers described feelings of “burnout” due to the unequal demands of home and work. With the World Health Organization defining burnout as a condition resulting from “chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed”, organizations should note its impacts: fatigue, decreased mental wellness, as well as reduced work productivity, motivation, and engagement, to name a few.

Image From: https://www.asuresoftware.com/blog/employee-anxiety-return-to-work

Image From: https://www.asuresoftware.com/blog/employee-anxiety-return-to-work

The added demands of a pandemic-induced recession such as increased caregiving, virtual schooling, stress due to the changing nature of work, and fears of job security makes this condition one that employers can no longer ignore (Landau, 2020). As COVID-19 continues to take a toll on daily life, with schools, childcare, health care, workplaces, and the economy being affected, studies conclude that to adequately support and retain women and female-identified caregivers, employers must double down on their strategies for supporting and retaining women (Maven Clinic, 2020).

LMU SOE Associate Dean Dr. Yvette Lapayese, professor in the Department of Teaching and Learning in the LMU School of Education and author of the critical education chapter, “Mother-Scholars: Thinking and Being in Higher Education” (2017), highlights an urgent call for action at the university level. “Universities are missing a critical opportunity to confront caregiving as a gender equity issue – an issue that deepens when factors related to income level, race and ethnicity, gender identity, sexuality, non-traditional family structures, and ability are added to the equation.” According to Lapayese, “Many universities have largely ignored the fact that female-identified caretakers confront this impossible situation daily – working full-time and providing full-time care to their dependents.” Instead of using the COVID-19 crisis as a turning point to reimagine a more inclusive and caring system, however, she notes what a recent Inside Higher Education (2020) article documenting university efforts during COVID-19 highlights: that many universities have proceeded with “business as usual.” “Sadly, this includes universities that shout social justice from their rooftops,” she notes.

Some local universities have made progress in considering new policies to support women and enlisting university administrative support. UCLA’s Center for the Study of Women, for example, put forth an initiative that urged UCLA administrators to ramp up a COVID-19 childcare support program addressing, “through a variety of creative and diverse solutions, the array of work-related impacts to caregiving faculty, graduate students, and staff as a result of closures of care facilities” (Flaherty, 2020). In an open letter petition last summer signed by over 40 UCLA faculty, the center concurred with the assessment that their essential worker status, coupled with the childcare and school vacuum, leaves academic caregivers in an “impossible situation.” The UCLA initiative would target those workers who find themselves with an increased (at least 50 percent) caretaking responsibility for one or more children under 12, children of any age with a disability or illness and an adult dependent with an illness or impairment (Flaherty, 2020).

Women faculty from the California State University system also drafted an open letter representing the California Faculty Association, the union that represents faculty in the 23-campus system. The open letter was sent to the chancellor asking the CSU system to provide teaching assistants or paid leave to ease their load, including helping to educate children learning from home or caring for elderly family members. Negotiations continue between the union and the CSU system (Smith, 2021).

Where to begin? First, accurate data on how the pandemic has impacted female-identified caregivers and women – and making this data accessible and transparent – is essential. How many women have left LMU since the pandemic began one year ago? Why? Has it been the lack of perceived support or policies that allow them to work while shouldering responsibility for childcare/elder care? How many have been furloughed or released? Prompt and transparent utilization of data can go a long way in establishing a roadmap of priorities to support and retain working female-identified caregivers during the pandemic. As one LMU female working mother employee, Rebecca Okida, LMU Student Affairs resident director and LMU Committee on the Status of Women (CSW) member, puts it: “How can we expect to recruit and retain women if there is not readily available, transparent data on equitable compensation and female advancement within our institution?”

Using this data, Okida suggests, can enable university administrators to act quickly to set up new policies specifically designed to address this population: “They can address pay parity, provide transparency in decision-making, hiring and furlough practices, and address the disproportionate ways that campus increases in cost for childcare, parking, and even the gym on campus affects us as female-identified employees and parents,” Okida notes.

Given the newly formed DEI committees and initiatives across the university that aim to break down white supremacy and racist ideologies and to promote the hiring, support and retention of BIPOC colleagues, establishing measures to address gender inequities within DEI efforts seems to be a natural fit. The Maven Clinic’s recent “best practice” report concludes that supporting working parents should be a critical goal for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion efforts: “Employers need real, proven strategies and solutions, and they need them now…. What stands out are real investments in stretched populations that help attract and retain diverse perspectives at all levels.”

Although she acknowledges that the pandemic is an evolving situation, Lapayese agrees with the need to address gender equity right now – there simply is no more time to lose. “One easy next step is for university administrators to immediately implement a waiver on all non-essential services for university employees until child-care, elder-care, and other dependent-care issues are resolved for female-identified caretakers.” For faculty, these non-essential services could be excusing faculty for work on curriculum reform and attendance at non-essential faculty meetings, for example.

Okida notes that LMU can also implement what other universities and organizations committed to supporting woman and caregivers during this crisis are doing. “LMU has an opportunity to actively demonstrate their support for their commitment to ‘care of the whole person’ by providing childcare benefits for working parents; by creating explicit policies that support flexibility such as reduced hours while maintaining benefits, granting an hour per day of ‘COVID-related administrative leave’, and designated specific days as ‘meeting free’; and by hiring more woman at the executive/administrative level.”

More than ever, Lapayese notes, we need university leaders to enact gender equity-focused policies driven by compassion and inclusivity – which are typically hallmarks found in the written mission of many of today’s higher education institutions, yet in today’s pandemic world have yet to translate into equitable action. “The silence and lack of action by university administrators around the shuttering of schools and childcare facilities begs the question – how many high-level, decision-making university administrators are female-identified caretakers? This missing perspective at the ‘top levels’ may be part of the issue.”

Even without high-level representation, however, Lapayese notes that universities do have in-house academic experts and researchers who can help design clear, campus-wide policies that offer flexibility for faculty, staff, and students in navigating the simultaneous responsibilities of caregiving, health care needs, and work responsibilities. “Policies that support our first-generation female-identified students, for example – many of whom may need to care for grandparents, younger siblings, partners, and other family members during this time — should be at the forefront of the conversation,” Lapayese says.

With many female-identified caregivers being disproportionately affected – experiencing the burden of a yearlong pandemic, isolation, and uncertainty, and now reduced support for childcare, education, and mental health – many caregivers are at the end of their rope. “It’s time for LMU to put action behind their Jesuit values and implement tangible policies that reflect cura personalis and the belief that working women are essential here,” says Okida.

Lapayese agrees: “Ultimately, university leaders who remain silent and immobilized regarding the workload, role overload, and trauma that female-identified faculty, staff, and student caretakers are experiencing is unpardonable,” she states. “Their lack of action may be taken to indicate that patriarchy has tightened its grip on the university during this time of crisis.”

Access list of references here.

OIA Buzz

- Watch Now:

The President’s Office and Intercultural Affairs present on their Systemic Analysis processes; March 2, 2021.

Register for the next Systemic Analysis Report Out Session on March 16, 2021, where the School of Film and Television and the Institutional Research and Decision Support office will present.

- Review and Learn:

Celebrate Women’s History Month at LMU: https://www.lmu.edu/whm/

LA Loyolan Exclusive Interview: Dr. Joan Wicks, mother of inaugural poet Amanda Gorman, shares with the Loyolan why LMU is such a special place for her entire family.

The third Community Check-in survey will be available to complete March 15-26.

- Attend:

“A Faith that does Justice: Interfaith Perspectives.” On March 19, from 2-3:15 p.m., we will hold an interfaith liturgy, featuring Dr. Marla F. Frederick, Asa Griggs Candler Professor of Religion and Culture at Emory University.

Join us for the next Systemic Analysis Consultation Workshop and receive access to the Systemic Analysis Brightspace course, which will provide a systemic analysis guidebook and equity scorecards for student, staff and faculty. The next workshop is on March 12, from 2-3 p.m.

To learn about pathways to a Ph.D. in business, register for Higher Learning: The Path to a Ph.D., March 12, 2021 at 1 p.m. EST. Hosted by The PhD Project and KMPG.

- Submit:

Reminder that all units are encouraged to submit a Progress Report. Units who are submitting for the first time or those who are providing updates to previous work are invited to do so by March 10 in order to be included in the spring semester update to OIA’s Data & Accountability website, which is now live and reflecting unit progress. Several units are doing excellent work in this area but have not yet submitted their reports (and are encouraged to do so).

- Share:

With the LMU Anti-Racism Project’s In Six Words series, we hope to spark conversation, understanding, and empathy across all identities. March stories will highlight the joys, struggles and ways of overcoming obstacles for all people who identify with the gender of women, inclusive of gender fluidity.

This week’s example story, by Dr. Magaela Bethune, assistant professor of African American Studies, speaks to the importance of intersectionality and empowerment:

“My Blackness … womanhood … breath … is Resistance.”

Dr. Bethune says: Every breath I take is a miracle. Every inspiration and expiration I make at the intersection of my Blackness and my womanhood – is resistance. Is revolution.