By Hillary Henderson,

Administrative Specialist for Intercultural Affairs

There is much to improve upon the way that American history is taught in society and education. For much of our history in the United States, the perspectives and experiences of marginalized groups have been a footnote; an invisible asterisk to the “main” story. We can trace many of our current cultural history and heritage months to the 1960s (when some might say civil rights first began). What we must acknowledge as a society is that the history of marginalized groups — the good, the bad, and the oppressive — is what makes our country what it is today.

It is important for people of marginalized groups to see themselves reflected in and throughout curriculum at all levels of education, from pre-K to doctorate programs. In addition, telling our histories is important to foster intergroup dialogue and understanding. We are valued members of society, and thus our stories need not be “othered” or specialized as different categories of knowledge. Ideally, society will one day recognize that just as individuals have intersectional identities, American history is, in itself, intersectional. We wouldn’t limit ourselves to specific months for exploring the struggles and achievements of BIPOC, immigrant, and LGBTQ communities; rather, accounts of our narratives would be engrained into all aspects of our education.

This kind of change begins, of course, with learning. Consider this a brief (and not comprehensive) American history lesson that centers and celebrates lesbians, gay, bisexual, pansexual, demisexual, and asexual individuals, transgender men and women, intersex people, those who are non-binary or gender-nonconforming, and all who identify as queer or questioning.

—

It is not easy to pinpoint where LGBTQ history begins in America (or the world, for that matter). Though a Google search of “Who was the first gay caveman?” does yield some interesting results, it may be common to begin with the ancient Greeks — and more specifically Sappho, a legendary Greek poet and lyricist who often wrote about love and desire between women, and was exiled to her home island of Lesbos; and Plato, whose famous work, “The Symposium,” introduced theories of love that suggested fluid sexuality among men and women. After a gap of time where LGBTQ stories scarcely exist on public record, the history continues through repression, oppression and research. Society in the 1600s condemned homosexuality (considered “sodomy” back then) and established a norm of death penalties and corporeal punishment for gay men and women. Through the Colonial to the Victorian eras, there were more instances of prosecution for homosexuality in addition to scientific and medical exploration of human sexuality.

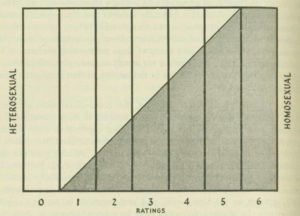

Havelock Ellis (1859-1939) is noted as an influential physician who, in his studies and writings, asserted that homosexuality is natural, paving the way to LGBTQ reconceptualization. His noted work, “Studies in the Psychology of Sex,” was published between 1897 and 1928. This was later followed by Alfred Kinsey, who created the Kinsey Scale (1948), introducing a concept of sexual fluidity and proved that homosexuality was more common than expected.

In the 1920s through the 1960s, the topic of homosexuality saw more public discussion and members of the LGBTQ community across the country began to assert their claim to basic human rights. During the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s, gay life prospered in metropolitan communities such as Greenwich Village and Harlem in New York. African American blues artists shared music pertaining to lesbian desire, struggle, and humor. Many speakeasy clubs hosted a hidden world of gay pride that emerged through music, art, and the growing popularity of male and female drag stars. Organizations such as Society for Human Rights and The Mattachine Society were growing despite pushback from U.S. state and federal governments.

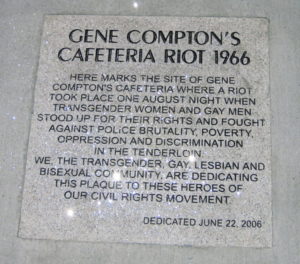

The Civil Rights era saw the “first American-based political demands for fair treatment of gays and lesbians in mental health, public policy and employment” (APA.org). One of the earliest gay rights demonstrations can be traced to New York City in 1963, at the Whitehall Induction Center. San Francisco of 1966 saw the first, though little-known riot at Compton’s Cafeteria. On June 28, 1969, a bar in New York City called the Stonewall Inn — popular among the LGBTQ community — was raided by police. Though it was not the first time a gay bar was targeted, it was evidently the last straw for LGBTQ citizens. Led by Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera — trans women, sex workers, founders of STAR, and iconic historical figures of this era — the patrons of Stonewall Inn fought back and sparked a series of protests and demonstrations that fueled the LGBTQ civil rights movement.

Coined the Gay Liberation Movement, this was a period of activism, organization, and the beginnings of reform. Illinois became the first state to repeal sodomy laws in 1962, and other states began to follow suit. One year after the Stonewall Riots, activists and allies commemorated the event with a march through the streets. This was coined Christopher Street Liberation Day, and is noted as the first ever gay pride parade. In 1987, there was a national march on Washington for lesbian and gay rights; a year later, Rob Eichberg and Jean O’Leary enacted the first National Coming Out Day, which is still recognized every year on October 11. Same-sex marriage was first legalized in Massachusetts in 2003. After a long cycle of activism and pushback, and individual state legalizations, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled to legalize same-sex marriages in all 50 states, in the Obergefell v. Hodges case of 2015.

Our history does not end at the legalization of same-sex marriage; nor does the fight for all rights to be recognized. There is plenty more history to be shared here, such as (but not limited to) the HIV/AIDS epidemic of the 1980s and early 90s; the “Lavender Scare;” persecution of gay men during the Holocaust; U.S. military policy and discrimination; LGBTQ representation milestones in media, theater, and art; and more recent events signifying both pain and victory.

Though the U.S. has come far, there is still, and always, much work to be done. Each year, we celebrate Pride Month in June, and LGBTQ History Month in October not only to commemorate our successes, but to honor the countless victims of hate crimes, the transgender men and women of color who constantly battle forms of discrimination and abuse, and the LGBTQ youth who deserve home, family, love, and a life without shame.

Uplifting our stories and sharing our history — this country’s history — is just one way to recognize Pride and educate others about who we are and how far we have come. In “Pedagogy of the Oppressed” (1970), Paulo Freire states, “There’s no such thing as neutral education. Education either functions as an instrument to bring about conformity or freedom.” Everyone in our community at LMU — faculty, students, staff, administration — has a responsibility to share and receive education in a way that moves us all toward a more equitable and inclusive society. We can all do our part by learning about different cultures and exploring a more full and inclusive history of our country.

OIA Buzz:

a) Take some time to learn about some of these LGBTQ ‘MVPs’ in American history:

Marsha P. Johnson, Sylvia Rivera, Randy Wicker, James Baldwin, Harvey Milk, Audre Lorde, Bayard Rustin, Laverne Cox, Gladys Bentley, Storme Delarverie, Christine Jorgensen, Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, Larry Kramer, RuPaul, Janet Mock, Gilbert Baker, Michael Sam, Elliot Page, Lil Nas X, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Big Freedia

Note that this is not an exhaustive list.

b) Celebrate Pride, 24/7 and 365: LMU’s Pride Month hub is available to view now.

c) Pride Art: Call for Submissions

As part of our celebrations, we want to showcase the artistic expressions of the LGBTQ+ community and allies. We invite LMU students, faculty, staff, and alumni to submit an artistic work to showcase on our Pride Month hub.

Submit any original and creative piece that represents the beauty, strength, diversity, and PRIDE for LGBTQ+ identities. We encourage variety, including:

-

- Visual Art – drawings, paintings, digital and graphic designs, photography, sculptures

- Written Works – poetry or prose

- Musical contributions

- Video – dance performances, skits, videography, etc.

Complete this form and upload your artwork to share your pride with LMU!

d) Cultural Consciousness Conversations is recruiting for its third annual cohort, 2021-22. The yearlong program is a project of Intercultural Affairs in collaboration with Ethnic and Intercultural Services. This cohort of faculty, staff, and administrators from various divisions around campus get together once a month to share stories, learn from one another, examine societal norms and cultural differences, and deepen connections across all sectors of the LMU community. Complete the interest form to learn more and sign up.

e) In Six Words

With the LMU Anti-Racism Project’s In Six Words series, we hope to spark conversation, understanding, and empathy across all identities. These stories will highlight the joys, struggles and ways of overcoming obstacles for all people who identify with the gender of women, inclusive of gender fluidity.

This week’s example story is by Jamal Epperson, resident director in the Student Housing Office.

“Assimilation cannot hold back our authenticity.”

Jamal writes: So often we’re so worried about how others perceive us that we can get lost when we have to see ourselves without the filters. When we allow ourselves to no longer assimilate to others’ ideals, we can feel their pressure and expectations lift off us. As you feel safe, allow yourself to stop code-switching, internalizing projections, and making yourself digestible to the guilt of others. As Megan Thee Stallion once said, “Once you really know yourself, can’t nobody tell you nothing about you.”